Bias is a fact of life. Our view of the world is colored by preconceptions, limited or mistaken information, and recent experience. On top of that limited and distorted impression, we then have to deal with a number of well-known systemic flaws in how we think, as discussed in Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Bias is a fact of life. Our view of the world is colored by preconceptions, limited or mistaken information, and recent experience. On top of that limited and distorted impression, we then have to deal with a number of well-known systemic flaws in how we think, as discussed in Daniel Kahneman’s book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

I’ve been thinking a lot about biases recently, with an eye to how to mitigate their effects. Right now, several cognitive lenses could be distorting what we see. Among them, there’s:

- Recent poor economic performance, which might cause us to miss signs of growth

- Lingering fear of another collapse, as we remember the pain of 2008

- Bias toward U.S. investments, driven by the recent outperformance of the S&P 500

How can we outmaneuver our weaknesses and blind spots?

You probably won’t be surprised to hear that my own solution is data. But before you get to data, you need to ask the right questions. Identifying them is surprisingly easy: just take one of your assumptions—the economy is doomed, for example—and ask what else would have to be happening if that were true. Then go and see if it actually is. Let’s look at a few examples.

Economic performance. An immediate example is the weak economic performance over the past couple of quarters, which now appears to be passing. You could (and many did) conclude that we were moving back into recession. The problem was, when you looked at the actual data, as I do on a monthly basis, none of the metrics that have historically heralded a recession were in the danger zone. Employment would have been dropping, but it wasn’t. Consumer confidence would have been going down, but it wasn’t. The Fed would have been raising rates, but it wasn’t. And so forth.

Inflation. Another immediate example is inflation. Although it has been and continues to be low, inflation is moving back up. We also know why it was low—low energy prices—and we know that is passing. For all the worry about deflation, especially here in the U.S., we can expect to see inflation move higher over the next 12 months as oil prices increase and wage growth accelerates. If we had a real deflation problem, asset prices, such as for real estate and the stock market, would be dropping, and they aren’t. Wages would be flat, but they’re not. And so forth.

The labor market and wages. For the past five years, we’ve heard about how bad the job market is. No jobs, bad jobs, people unable to get back into the workforce. That was true enough at one point, but it no longer reflects the very real improvements we’ve seen. Indeed, in many respects, the negative spin undermines confidence and prolongs the problem. In fact, we continue to see strong job growth, in good jobs, over time, and now wage growth is responding.

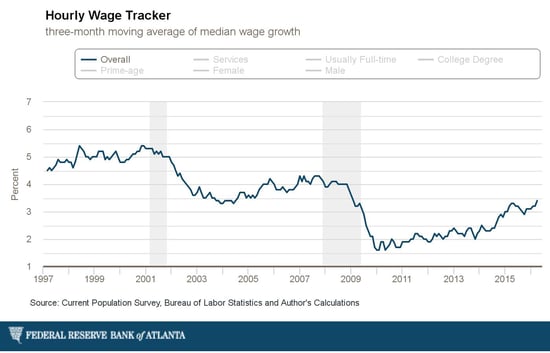

The things we'd be seeing if the labor market were actually bad just aren’t showing up. Take a look at how an independent observer, the Atlanta Fed, is showing wage growth in the following chart.

In other words, for all the negative biases out there, the news so far is actually pretty good.

The U.S. dollar. We've seen exactly the same behavior around the value of the U.S. dollar over the past several years. As the dollar weakened, many expected it would crash, with China taking over as the reserve currency. In fact, the dollar strengthened to uncomfortable levels, leading to fears that it would strangle the U.S. economy—only to return to more normal levels.

Keeping an eye out for changing trends

It’s when trends are scariest that they most affect our behavior—and are also most likely to be changing. The goal of this blog, in many ways, is to lean against these biases, to look at the big picture and say, No, the economy is pretty solid. No, inflation is coming back. No, the dollar is healthy and here to stay.

On the other hand, we also need to watch the trends and try to determine when they are changing, which is why I track both economic and market risks. At some point, we will need to take the conclusions discussed here and reverse them, to change our calls based on new evidence.

This is the essence of managing your biases—always looking for reasons you need to change your mind. Actually doing so, of course, remains the hard part.

Print

Print