We closed yesterday's post with the idea that the U.S. has been the indispensable market for all rising economies since WWII—starting with Europe under the Marshall Plan and then extending to Japan and subsequently to China and eastern Europe. As the essential market, the U.S. could compel obedience in other areas, notably security, and other countries were happy—or at least willing—to comply.

We closed yesterday's post with the idea that the U.S. has been the indispensable market for all rising economies since WWII—starting with Europe under the Marshall Plan and then extending to Japan and subsequently to China and eastern Europe. As the essential market, the U.S. could compel obedience in other areas, notably security, and other countries were happy—or at least willing—to comply.

That indispensability is at the core of the current U.S. trade strategy. China, the logic goes, depends on the U.S. market. So, by imposing tariffs and other restrictions, the U.S. can force policy changes. China won’t like it but will have no choice but to comply or else face an economic collapse.

All of this is consistent with history and makes a certain amount of sense. But with China rising both economically and militarily, the question is whether the Chinese believe it as well. Or does China think it has passed the point where it no longer needs the U.S. as a market? So far, China has not folded its hand, suggesting that it thinks it can prevail.

Just in case, of course, the U.S. is also using its clout with other countries to try to lock them into the U.S. coalition. The new North American trade deal has a clause that allows the U.S. to terminate the agreement if either Canada or Mexico cuts a deal we don’t like with a nonmarket economy—meaning China. We are also leaning on Europe and other trade partners to take our side. If the U.S. has an advantage, that advantage gets much bigger with the other developed economies on our side. Will they actually be there, though? That depends on their own self-interests, and that is where we are right now.

How will this play out? Let’s take a look at the numbers to see what we can learn.

Global trade

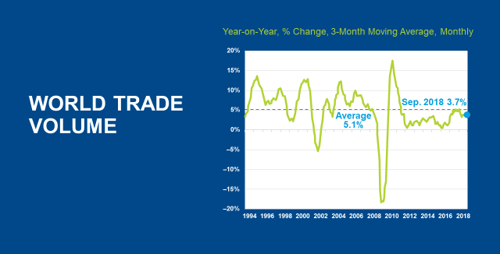

The first question is to decide who is most exposed to the conflict. Who has most at risk? That will be the party that will probably have to blink first. Looking at the big picture, we can see that beyond the recent trade confrontations, global trade as a whole has been growing more slowly over the past several years than it had recently. In fact, since 2011, global trade growth has never exceeded the average level of the prior couple of decades. This has had a material effect on economic growth elsewhere in the world, including China.

Source: FactSet, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, Netherland Policy Analysis

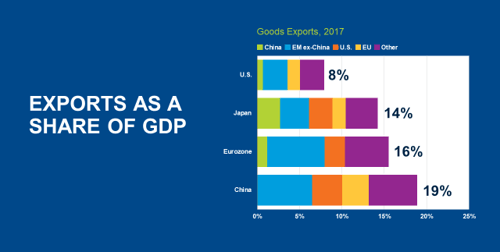

You can see why that is from the next chart. China derives almost one-fifth of its economy from goods exports. Europe about one-sixth, and Japan about one-seventh. The U.S., on the other hand, is much less exposed than any of its competitors or partners. China’s reliance on exports is more than twice that of the U.S., and Europe and Japan are about twice as much.

Source: FactSet, J.P. Morgan Asset Management, IMF, Guide to Markets – U.S. Data as of September 30, 2018.

In terms of both who is at risk and who has the leverage, you can clearly see that the U.S. remains a critical market, at about 4 percent of China’s and Japan’s GDP and about 3 percent of Europe’s. When you compare relative demand shares, you can also see that the U.S. is about three times as important to Europe as China is and that the Chinese exposure and U.S. exposure are about the same for Japan. Overall, the U.S. is clearly the more important market. As such, we have the leverage to try to force other players onto our side.

Does the U.S. have an advantage?

There are also geopolitical and macroeconomic implications. Japan, for instance, has roughly equal export exposure to the U.S. and China but is much less militarily threatened by the U.S., and it has an alliance to boot. Europe is more economically exposed but also has an alliance structure with the U.S.

Beyond these factors, though, both Japan and China are developed economies, like the U.S., specializing in high-tech. So, they have the same concerns about a rising China that the U.S. does around intellectual property protection and open markets. They don’t want China as a developed competitor any more than the U.S. does and so have yet another reason to side with the U.S.

Given all of these factors—the economic weight of the U.S., in both relative and absolute terms; the existing geopolitical alliance structure; and the macroeconomic commonalities among the developed economies—the U.S. does indeed have an advantage. It remains the necessary market, especially in combination with its partners.

Foreign reserves

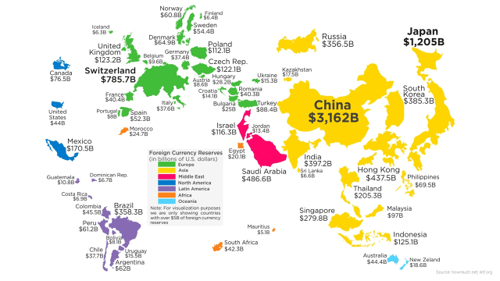

One additional way to look at this relative strength is to consider holdings of foreign reserves. The map below shows that China and Japan both hold large amounts. But the really interesting thing? The U.S. holds, essentially, none. How can that be? The answer is that China and Japan don’t choose to hold foreign currencies, but they have to. The U.S., on the other hand, can trade in dollars. Controlling the medium of trade is just one more lever the U.S. has available, but that control itself reflects all of the other advantages as well.

Collateral damage

The U.S., then, will probably end up prevailing, in some form, in the current trade conflict. It is likely to be messy, however. Even with a “win,” there is and will continue to be collateral damage. The real question going forward is what that will mean for our investments. We will take a look at that next week.

Print

Print