We closed the last post in this series on the note that while the now world (i.e., the world we live in) has benefited enormously from the economic freedom that came with the new world, changes are underway that might limit that freedom—to our economic detriment. As politics comes to the fore again, economics may once again take second place.

To begin, let’s go back to the map we started with, with all of its embedded assumptions. This is the world we live in today, at least from a U.S. perspective. It is not, however, how China sees it.

China, I suspect, sees the world something like the map below.

Note the embedded assumptions here: this is still one world, economically open. But here we see China at the center, with everything else revolving around it. This is the world China would like to see. It is one where it can benefit from free trade and everything that goes with it, but China clearly dominates the world. In other words, China likes the world as it is but wants to change places with the U.S.

A world divided

China has history and demographics behind it. For millennia, China was the largest and most advanced society in the world. Indeed, China often refers to itself as the Middle Kingdom, the land at the center of the world. China is also the world’s largest country by population. From a Chinese perspective, China should be at the center of the world.

The U.S., of course, doesn’t see it that way. And this is where we find ourselves right now. As China and the U.S. face off, the structure of the world could become increasingly political. In the end, we could find ourselves, once again, in a world divided by politics. Companies would face smaller markets and less available and more expensive labor and capital. Business conditions—interest rates and stock valuations—could find themselves retracing the path of the past 40 years, back to the levels of the old world.

This is not, however, an immediate problem. The immediate problem is how the confrontation is likely to evolve in the short term, which will determine whether we have a bigger problem in the long term. Here, we have some data that can help us figure that out.

Headed toward a war?

The first option—and one that has generated an increasing number of headlines—is war. China and the U.S. are, the headlines go, locked in a “Thucydides trap,” so named for the Greek historian who described the wars between a rising Athens and Sparta. When a rising power confronts a dominant power, the narrative goes, the only possible outcome is war. The most recent example, from the last century, is Germany and Great Britain. With China rising and the U.S. unwilling to give way, will they have to fight it out?

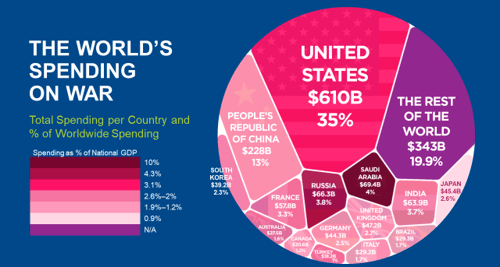

If they do, the U.S. has an incredible advantage, not just in forces but also in operational experience. As the chart below shows, from a spending point of view, the U.S. outweighs everyone else—including China. This also does not take into account the U.S. allies, including Japan and South Korea, as well as Taiwan. China is certainly building up its military power, but it is not there yet. A war is likely at least a decade away, if it ever happens.

Source: howmuch.net

Back to the old world?

Instead, the confrontation, as we are seeing, is likely to be political and economic. For China to continue its rise, it will need to maintain and expand its economic growth and international presence. How—and whether—it can do that, and what the U.S. does in response, will determine whether the next world reverts to the old world or not. We will take a look at that next.

Print

Print