The last post in this series was about the old world, one that was dominated and defined by politics both between and within nation-states. Indeed, the nation-state was the defining entity of the period, with political borders determining economic relationships. But even within nation-states, economic actors were largely constrained by political forces, in the form of laws, regulations, and borders. It was a much smaller world from the perspective of most companies. Your competitors came from your industry, in your country. You knew them, they knew you, and you were all pretty much playing by the same rules and subject to the same constraints.

The last post in this series was about the old world, one that was dominated and defined by politics both between and within nation-states. Indeed, the nation-state was the defining entity of the period, with political borders determining economic relationships. But even within nation-states, economic actors were largely constrained by political forces, in the form of laws, regulations, and borders. It was a much smaller world from the perspective of most companies. Your competitors came from your industry, in your country. You knew them, they knew you, and you were all pretty much playing by the same rules and subject to the same constraints.

When China opened and the Berlin Wall came down, all of that collapsed—although no one realized it at the time. When walls came down, the expectation here in the West was that the flow would go one way—that “they” would adopt “our” ideas and become like us. Although that certainly happened, “they” also changed “us.”

Opening markets

The first and, in many ways, best example of this change is the auto industry. For decades, the U.S. auto industry was a cozy oligopoly, where competitors knew one another and were subject to the same constraints. But in the 1980s, that industry was blown up by Japan. The Japanese didn’t manufacture or do business in the same way, and they were not subject to the same constraints. Given a chance, through opening markets, they proceeded to eat Detroit’s lunch. That story was repeated again and again in different industries with different countries. It wasn’t all against the U.S., of course. Even as the U.S. lost ground in some areas, we gained ground in other, generally higher value-add areas. With markets opening, we got the chance to do to others what Japan was doing to us—and did so.

Cheaper goods and services

The net effect was that consumers around the world got a wider array of cheaper goods and services (cars, TVs, and everything else), while companies had to be more competitive. They could be more competitive, though, as they now had access to larger and cheaper labor forces around the world, larger markets to sell to, and more capital generated by the savings of foreign workers. Everyone benefited in some way, even if some bore the costs as well. The deregulation of many industries within countries had the same effects—and for the same reasons. Pretty much everything you now do, economically, is better and cheaper than it was in the old world.

Old world versus new world

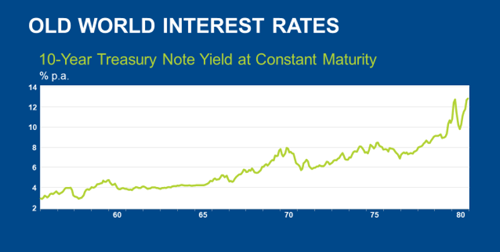

From a macro perspective, the difference between the worlds is very clear. In the old world, with its limits on labor and capital, economies faced rising constraints that forced inflation and interest rates higher over a three-decade period. In fact, interest rates rose by over five times during this time.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Haver Analytics

With rates rising and company profits hit by the same constraints, we also saw stock market valuations declining over the same period. From the peak, the average valuation level was down by more than 50 percent. The old world was a tough place to do business or to invest, no doubt about it.

Source: Standard & Poor's, Haver Analytics

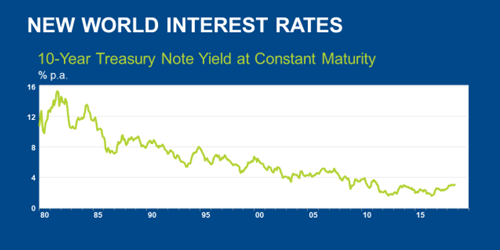

In the almost four decades of the new world, however, we have seen just the opposite. A flood of new labor, free movement of capital, and deregulation have removed many of those constraints. Interest rates have dropped over almost that entire time period, back to the initial levels of the old world. This drop reflects the superior economic environment, to the benefit (as we have seen) of both business and consumers.

Source: Federal Reserve Board, Haver Analytics

Stock valuations have turned around as well (almost quadrupling), reflecting the better economic and business environment, as well as lower interest rates. Yes, there have certainly been some peaks and valleys along the way, but the trend in both cases has been clear. The new world has largely reversed the trends of the old world, to everyone’s economic advantage.

Source: Robert Shiller, Haver Analytics

Economic freedom

How did this reversal happen? There has been one foundation, enabled by the absence of political constraints: free trade in goods, in labor, and in capital. This economic freedom allowed individuals, companies, and countries to drive growth across the board. It allowed the theory of comparative advantage—where different economic actors specialize in what they are best at for the good of all—to become the reality of comparative advantage. This is the foundation of the new world and all the economic benefits we now take for granted. After several decades, this world is all most of us have known.

The next world

I started this series with the idea that the world might indeed be changing. If so, then things really could be different this time. As we look forward, there are real signs that the next world might be significantly different from the new world. In fact, as politics becomes a greater actor around the globe, the next world might look more like the old world than the new one, with all that that implies. We will talk more about that next week.

Print

Print