Yesterday, we talked about the deficit and debt. We came to the conclusion that a modest deficit was not necessarily a problem. But the increase in the debt in recent years—and, this year, in the deficit—made both a problem that will have to be dealt with.

Yesterday, we talked about the deficit and debt. We came to the conclusion that a modest deficit was not necessarily a problem. But the increase in the debt in recent years—and, this year, in the deficit—made both a problem that will have to be dealt with.

Now, the question I am usually asked is whether the deficit and debt are a problem. As noted, the answer is a definite yes. But the more useful question is whether they are a solvable problem. Fortunately, the answer here is also yes.

Remember the sequester?

Let’s start by thinking about fairly recent history: the fiscal cliff and the sequester. (If you’re a bit fuzzy, you can find a detailed discussion on Wikipedia.) Briefly, several years ago, the deficit was high and rising, and the debt was at new highs (much like today). But the U.S. Congress was unable to agree on what to do about it (again, much like today). In its wisdom, Congress decided to pass a law to force a compromise. This law was known as the sequester, which would automatically cut spending in the absence of an agreement. Such spending cuts, all agreed, would be so damaging that Congress would have to compromise. In fact, it didn’t work out that way. Congress could not come to a compromise (again, much like today!), and the sequester spending cuts took effect—despite the widespread expectation of incredible economic damage.

And you know what? They worked. The deficit dropped below the level of economic growth, which meant the debt stopped growing as a percentage of the economy. For all intents and purposes, the problem went away.

Faster growth, lower deficit

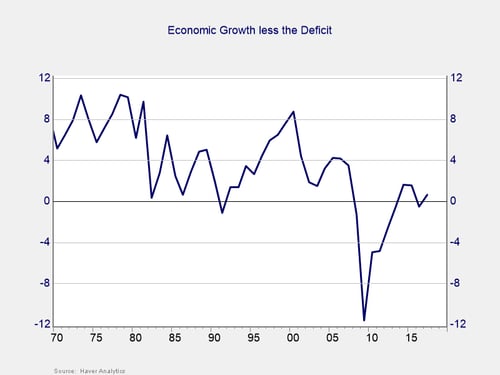

You can see this result in the chart below. Here, I subtracted deficit as a percentage of the economy from economic growth. When the economy is growing faster than the debt, which is to say the line is above the zero level, the accumulation of debt slows or reverses. When the debt is growing faster than the economy, which happened from 2009 to 2012, the debt grows. That dip below the zero level from 2009 to 2012 is what led to the rapidly growing deficit and debt and then to the fiscal cliff and the sequester.

After the sequester spending cuts, though, the deficit dropped and economic growth picked up, taking us back above the line. The deficit went away as a political problem. As an economic problem, it also moderated significantly, as faster growth allowed the lower deficits from the spending cuts. The sequester, in other words, worked.

Would it work again?

So, we know that not long ago, the U.S. faced a much worse deficit situation than we do right now. We also know that by cutting spending, we were able to effectively balance the budget after considering economic growth. If we did it then, we could presumably do it now as well.

The problem is therefore solvable—but it’s not that simple. In many respects, things are worse now than they were then. The debt is significantly higher. The deficit is now at levels previously seen only during recessions, despite the fact that we are in a decade-long expansion. In other words, because of the growth over the past decade, things look better than they are. At some point when we get a recession, we could see this chart drop down to levels close to those of the fiscal cliff. Then, we will need a combination of tax increases and spending cuts to get the budget back to something close to balanced, even when considering growth. This is not politics—it’s math—and it will hit both parties hard. Just as with the fiscal cliff and the sequester, a need to get something done will force both parties to take steps they hate.

A painful solution

This analysis also gives us a time frame to look at. Problems don’t get solved until the pain of the solution is less than the pain of the problem. It took about three years for the significant imbalances from the Great Recession to force congressional action. We will probably see something happen politically about three years from the start of the next recession, which is to say not for quite a while.

Print

Print