Just as I do with the economy, I review the market each month for warning signs of trouble in the near future. Although valuations are now high—a noted risk factor in past bear markets—markets can stay expensive (or get much more expensive) for years and years, which doesn’t give us much to go on timing-wise.

Just as I do with the economy, I review the market each month for warning signs of trouble in the near future. Although valuations are now high—a noted risk factor in past bear markets—markets can stay expensive (or get much more expensive) for years and years, which doesn’t give us much to go on timing-wise.

Of course, there are other market risk factors beyond valuations. For our purposes, two things are important: (1) to recognize when risk levels are high, and (2) to try and determine when those high risk levels become an immediate, rather than theoretical, concern. This regular update aims to do both.

Risk factor #1: Valuation levels

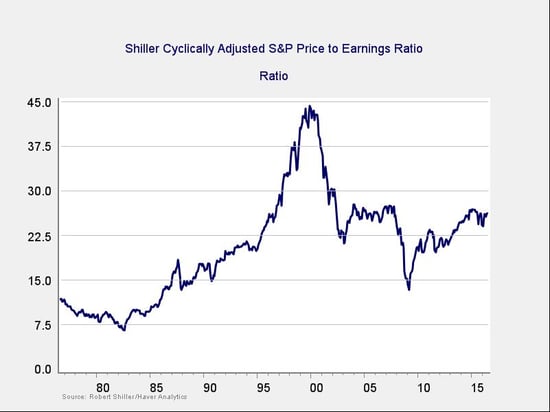

When it comes to assessing valuations, I find longer-term metrics—particularly the cyclically adjusted Shiller P/E ratio, which looks at average earnings over the past 10 years—to be the most useful in determining overall risk.

Two things jump out from this chart. First, after a recent pullback, valuations are again approaching the levels of 2007–2008 and 2015, where previous drawdowns started. Second, even at the bottom of the recent pullback, valuations were still at levels above any point since the crisis and well above levels before the late 1990s.

Although close to their highest levels over the past 10 years, valuations remain below the 2000 peak, so you might argue that this metric is not suggesting immediate risk. Of course, that assumes we might head back to 2000 bubble conditions, which isn’t exactly reassuring.

Risk factor #2: Changes in valuation levels

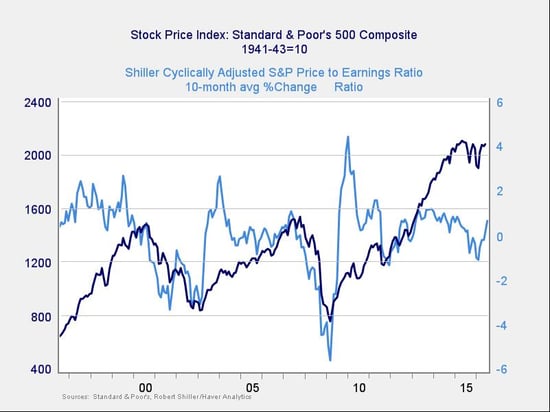

As good as the Shiller P/E ratio is as a risk indicator, it’s a terrible timing indicator. One way to remedy that is to look at changes in valuation levels over time instead of absolute levels.

Here, you can see that when valuations roll over, with the change dropping below zero over a 10-month or 200-day period, the market itself typically drops shortly thereafter. With the recent recovery, we have just moved back out of the trouble zone and continue to advance in the right direction. Although risks remain, they may not be immediate.

Risk factor #3: Margin debt

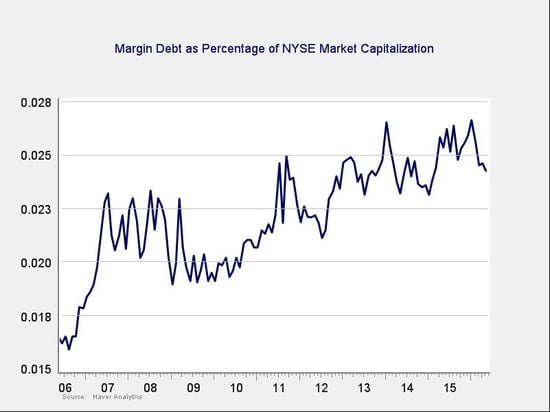

Another indicator of potential trouble is margin debt.

Thanks to the market recovery and some de-risking by borrowers, debt levels (as a percentage of market capitalization) have declined, although they still remain high. I think this continues to be an indicator of higher risk but, with recent improvements, not necessarily immediate risk.

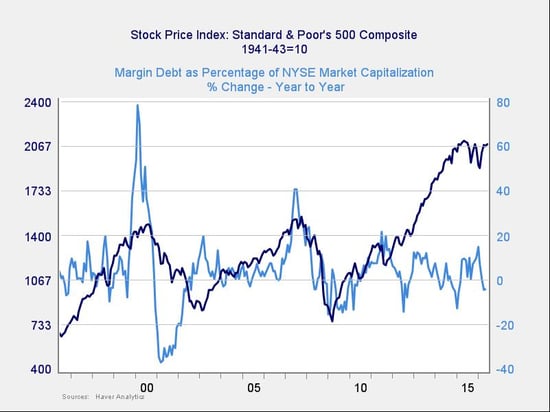

Risk factor #4: Changes in margin debt

Consistent with this, if we look at the change over time, spikes in debt levels typically precede a drawdown. Even as the absolute risk level remains high, the immediate risk does not, as the spike in debt that led the most recent pullback is coming down.

Though the absolute level of margin debt is high, and so is the risk level, the trigger seems to be getting farther away.

Risk factor #5: The Buffett indicator

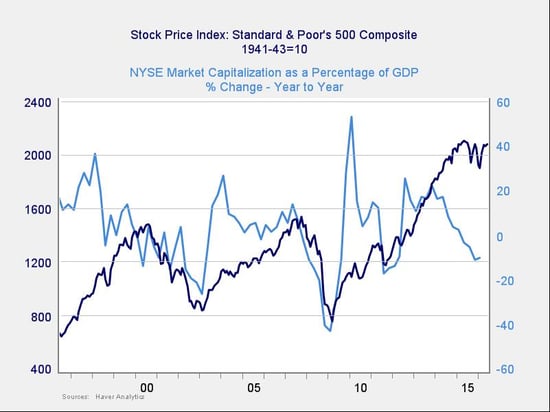

Said to be favored by Warren Buffett, the final indicator is the ratio of the value of all the companies in the market to the national economy as a whole.

On an absolute basis, the Buffett indicator is actually somewhat encouraging. Although it remains high, it has pulled back to less extreme levels. On a change-over-time basis, however, downturns in this indicator have typically led market pullbacks—and once again, we see that here. With the recent uptick, though, this indicator also suggests the risks are not immediate.

Technical metrics are also reasonably encouraging, with all three major U.S. indices well above their 200-day trend lines. Even as markets approach new highs, it’s quite possible that the advance will continue. A break into new territory could actually propel the market higher, despite the high valuation risk level.

On balance, all of the metrics are in what has historically been a high-risk zone, so we should be paying attention. But, as I’ve said many a time, there’s a big difference between high risk and immediate risk—and it is one that’s crucial to investing. As it stands, none of the indicators suggests an immediate problem, and several suggest risk may be receding.

Print

Print