As a follow-up to yesterday’s post about how no one seems to be worrying about the federal deficit, I was having a conversation with a reporter this morning and found myself expanding on other things the market seems to have forgotten about. Yes, we have the pandemic and the U.S. recovery on the radar, but not the deficit. And once you start thinking about it, there are other issues out there that were rattling markets only last year. What about the pending hard Brexit, for example? What about the U.S.-China trade conflict and deals? What about the continued weakness of the energy sector? What about the rising pandemic costs in emerging markets? What about the growing conflict between Greece and Turkey (two NATO countries) in the eastern Mediterranean? And so on, and so on.

As a follow-up to yesterday’s post about how no one seems to be worrying about the federal deficit, I was having a conversation with a reporter this morning and found myself expanding on other things the market seems to have forgotten about. Yes, we have the pandemic and the U.S. recovery on the radar, but not the deficit. And once you start thinking about it, there are other issues out there that were rattling markets only last year. What about the pending hard Brexit, for example? What about the U.S.-China trade conflict and deals? What about the continued weakness of the energy sector? What about the rising pandemic costs in emerging markets? What about the growing conflict between Greece and Turkey (two NATO countries) in the eastern Mediterranean? And so on, and so on.

Any one of these factors could have—and did—rattle the markets in the near past. Now, we have all of them coming to fruition at about the same time, in the middle of a global pandemic. And still, no one is paying attention.

We could take a deep dive on any one of these, but the individual issues are not the point. The point is the general complacency of the markets, which seem to be simply giving a pass to news that should be watched. Is this a problem? And how can we tell?

Complacency is a fuzzy term, and I don’t like fuzzy terms. So, let’s think about how we can quantify this concept. Once we have done that, we can then think about how to use it to help manage our portfolios.

The Complacency Metrics

There are two major metrics that relate to complacency. The first is stock valuations, that is, how much investors are willing to pay for companies. The more confident or complacent investors are, the higher the valuations.

The second metric is how volatile the market is. When investors are confident or complacent, volatility tends to go down, as they simply don't react to bad news. In a skittish market, bad news can really sink the market. So, low volatility is usually a sign of a complacent market.

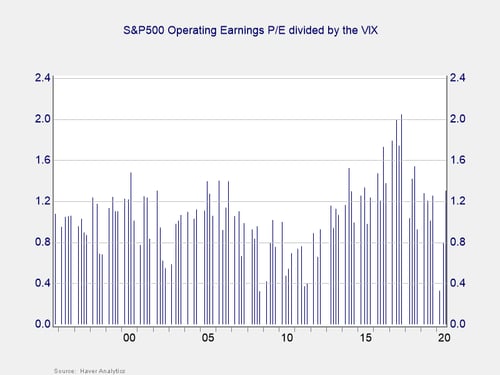

What if we combined the two? When investors are really confident, you would see very high stock valuations, combined with low volatility. To capture that scenario, I took the price-to-earnings ratio for the S&P 500, using operating earnings to avoid the spike due to the collapse in earnings during the financial crisis, and then divided it by the VIX, a stock market volatility index. By doing this, we have a combined number that captures how complacent the market is, as shown in the following chart.

You can see that this chart captures complacency reasonably well, peaking in 2000, in 2006–2007, and in 2017. In each case, we saw significant market drawdowns in the next year or so. Similarly, the low points historically have been a good time to buy.

Is the Market Too Complacent?

Looking at this, we can see that, surprisingly, the market does not seem all that complacent right now. Yes, valuations are very high. But we have seen enough volatility to pump the VIX up and take the complacency index down. The collapse in share prices at the start of the U.S. pandemic, as well as the more recent volatility, is keeping the VIX elevated and keeping the complacency index low. Right now, in fact, it is close to average levels after coming up in the past couple of months. Looking at this metric, the market seems to be less complacent than the headlines, or lack thereof, would suggest.

In fact, it looks like markets are more nervous than the headlines, or lack thereof, would suggest. This is likely a positive sign for the next couple of months, in that it may help limit the chances of future volatility. It will be worth watching, though, as valuations continue to increase and overall volatility declines. At the end of 2019, we were close to 2000 levels; in 2017–2018, we hit all-time highs. Valuations are now close to as high as they were then. If the VIX keeps going down, we could find ourselves in a high-complacency market again quite soon.

Print

Print