Yesterday, we looked closely at how the labor market has changed over the past couple of decades. Briefly, the number of job openings kept growing with the economy, while the number of unemployed people stayed roughly constant. As a result, the number of jobs available per unemployed person hit new highs and the number of excess workers—available workers less the job openings—went into deficit. Before the pandemic, there were more job openings than workers to fill them, for the first time. Currently, although the pandemic changed things temporarily, the labor market is back to worker shortage. As we look ahead to the next decade, will this trend continue?

Yesterday, we looked closely at how the labor market has changed over the past couple of decades. Briefly, the number of job openings kept growing with the economy, while the number of unemployed people stayed roughly constant. As a result, the number of jobs available per unemployed person hit new highs and the number of excess workers—available workers less the job openings—went into deficit. Before the pandemic, there were more job openings than workers to fill them, for the first time. Currently, although the pandemic changed things temporarily, the labor market is back to worker shortage. As we look ahead to the next decade, will this trend continue?

Retirement Trends

It will, and this is largely the boomers’ fault. (As a Gen Xer, I love saying that.) The baby boom generation is now fully aging into retirement. Pre-pandemic, many boomers kept working, slowing the decline in the available labor force. Then the pandemic forced many into retirement at last. What does the data show? After the initial pandemic layoffs, the number of people not working because they were laid off, in one form or another, steadily declined as individuals moved back into the workforce. The number of people not working due to retirement spiked, as older people who were laid off opted to remain out of the workforce.

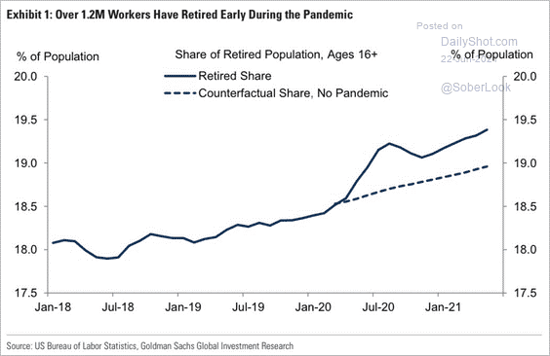

Overall, about 3 million people, or 1 percent of the population, have retired since the start of the pandemic. That number represents a substantial acceleration of the retirement trend. In fact, if we look closely at the excess retirements, there are about 1.2 million more people retired today than there would have been without the pandemic. This trend, which cuts directly into the labor force, explains a substantial chunk of the decline in available workers.

A Shock or a Trend?

When we look at individual components of the labor market, we can clearly see a significant demographic effect in the short term, driven largely by the acceleration in baby boomer retirement. If we look at this effect on a shock versus trend basis, however, it is far from clear that the labor force will continue to decline. The pandemic was a shock that took many boomers out of the labor market, but once they leave, that effect is done.

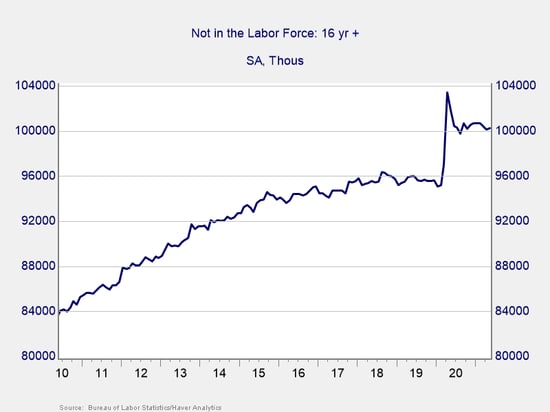

The chart above illustrates these demographics. At the start of the pandemic, we can clearly see the spike in people not in the labor force. Then, a partial recovery is evident. Of more interest, however, is what we have seen in the past year. The number of people out of the labor force has stabilized. This suggests that much of the damage has already been done—and that the excess retirements were indeed a shock rather than a change in trend.

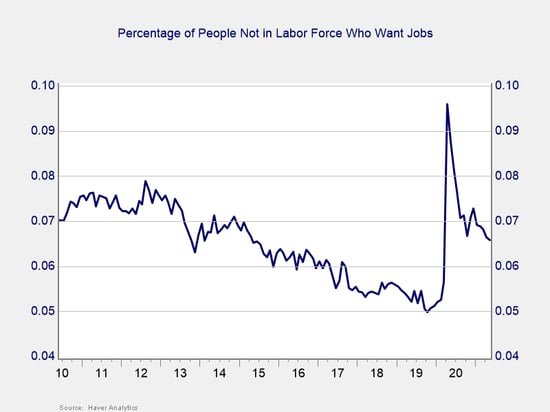

Shift in the Labor Market

But the data also shows that another trend—that of people moving and staying out of the labor force—is likely to continue. Although we have more people out of the labor force who want a job, that number is trending down again. It is matching the pre-pandemic trend line. Of the people who have left the labor force, an increasing proportion will not be coming back. We won’t see another series of shocks, such as those that occurred during the pandemic, but we won’t go back to the normal of past decades either. The labor market is in the middle of a shift from a surplus of workers to a potential shortage.

What will that mean for wages—and the economy as a whole? We will take a look at that next week. Have a great Independence Day, everyone!

Print

Print