Lots of things happened in 1987. Among others, I graduated from college. But, if you are in the financial industry at all, the mention of 1987 calls only one thing to mind: Black Monday (October 19, 1987), the day the stock market crashed. In many ways, this was the biggest nightmare of many stock investors. So, it is no wonder it continues to cast such a long shadow. In light of the recent market volatility, I think it makes sense to reflect on what happened 31 years ago today and what it might mean for investors today.

Lots of things happened in 1987. Among others, I graduated from college. But, if you are in the financial industry at all, the mention of 1987 calls only one thing to mind: Black Monday (October 19, 1987), the day the stock market crashed. In many ways, this was the biggest nightmare of many stock investors. So, it is no wonder it continues to cast such a long shadow. In light of the recent market volatility, I think it makes sense to reflect on what happened 31 years ago today and what it might mean for investors today.

Putting Black Monday in perspective

Let’s start with the magnitude of the decline: 508 points on the Dow. These days, 508 points doesn’t sound like all that much. After all, we saw the Dow go down more than that on two days last week. When we put that decline into percentages, though, it gives us a way to understand just what that drop meant. Back then, 508 points was a drop of 22.61 percent. In today’s terms, that would be more than 5,700 points.

In other words, Black Monday’s numbers would be about three times the decline we have seen over the past couple of weeks—all happening in one day. With the level of concern we have seen over a 2-percent drop in one day or 5 percent in one week, the panic back then would have risen exponentially. Indeed, it did. There was a real sense that things were coming apart—a sense that we didn’t see again until the great financial crisis of 2008–2009.

Volatility through the years

Much of the panic caused by Black Monday came from the perception that this crash was new ground, that there had never been a decline like this. On a daily basis, that sentiment was true. But looking further back in history, a dispassionate observer—not that there was one at the time—could have pointed to 1962. That year, the Kennedy Slide took markets down by 22.6 percent over a period of about six months, including the flash crash on May 28 when the Dow dropped 5.7 percent. There was a precedent, if you looked for it.

Since then, of course, there have been several other similar occasions. We had the intraday flash crash on May 6, 2010, when the Dow dropped almost 1,000 points (9 percent) in minutes, only to recover the same day. We also had the pullback in early 2016, when the Dow dropped 11 percent in a couple of weeks, and earlier this year, when the Dow dropped by more than 10 percent in a matter of days.

In the past decade, severe declines followed by rapid recoveries have become, if not common, at least usual. Of course, 1962 could be viewed as an outlier; 1987 was, other than 1962, unprecedented. Since then, however, we have seen this kind of extreme volatility play out several times. The question is, why?

Higher valuations, larger drawdowns

I suspect the answer is, simply, how expensive the market has become by historical standards. When you look at previous bear markets in history, which catches all of the significant declines, all but two were associated with economic recessions, as well as with other economic headwinds (e.g., rising oil prices or interest rates). That makes sense, as economic troubles reduce corporate profits, which should reduce share prices.

The two exceptions to this rule were 1962 and 1987. These crashes took place when the underlying economy was solid. In fact, the only risk factor they shared in common with the rest was that valuations were high by historical standards. Higher valuations, in the limited sample we have, seem to be associated with larger drawdowns that are not based on economic fundamentals.

We have also seen this more recently in smaller drawdowns—those that did not meet the 20-percent threshold for a bear market. I have already mentioned 2018 and 2016, and there are many others. Even if we don’t get the full 20 percent of a bear market, higher valuations do seem to be associated with a propensity for large, if short-lived, drawdowns.

This reasoning makes sense in a couple of ways. First is common sense: you can fall much further from the 10th floor than you can from the 2nd, so higher valuations simply give stocks more room to fall. Second, when valuations are high, they include a much greater confidence component, and confidence is simply more variable than the economic fundamentals. As such, stock prices should be more variable as well.

What does this mean for us today?

First, valuations are high, so the potential for volatility is very real. We have seen evidence of this in the past weeks, as well as several times in the past couple of years. Expect more volatility.

The second point is more complicated and relates to valuations overall. Right now, valuations are low by the standards of the past five years. Arguably, if those valuations are a good indicator of the future, any further downside should be limited. On the other hand, valuations are quite high based on times before the past five years. This indicates that if we move back to those conditions, we can potentially expect much greater downside risk.

For the moment I expect the first argument holds, but that may well be changing. We will be talking about that over the next couple of weeks.

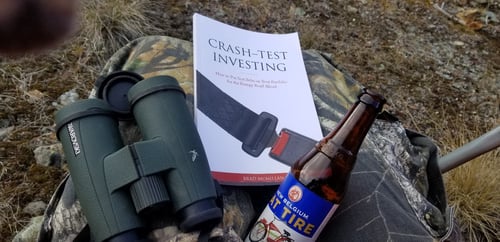

One final point. Given the recent volatility and our focus today on crashes, you might want to take a look at my book, Crash-Test Investing. It makes a great companion for trips, as reported by one advisor who took it out on a hillside in Colorado the other day. (Thanks, Bobby!) It also goes well with an adult beverage!

Print

Print