Recently, concerns about the velocity of money have resurfaced. Several readers have asked whether declining money velocity presages a crash, a recession, or something equally bad. It’s a fair question. As with many such issues, though, we’ve been down this road before several years ago. Low money velocity didn’t mean problems then, and it shouldn’t mean problems now.

Recently, concerns about the velocity of money have resurfaced. Several readers have asked whether declining money velocity presages a crash, a recession, or something equally bad. It’s a fair question. As with many such issues, though, we’ve been down this road before several years ago. Low money velocity didn’t mean problems then, and it shouldn’t mean problems now.

First, some definitions

Before we delve into the issue, we need to understand a couple of key terms.

Money stock: Conceptually, money stock is pretty straightforward—the total amount of money in a country’s economy at a given time. From there, however, it gets complicated. What counts as money? It should certainly include cash that people hold, but how about cash in banks? How about travelers checks? Bank accounts? Does it make a difference if the bank accounts are checking, which is available on demand, or savings, which may not be? How about money market accounts?

You get the idea. Nothing in economics is simple, but for our purposes, we can look at two of the most commonly used measures of money, known in the U.S. as M1 and M2:

- M1 includes cash in circulation, travelers checks, and checking accounts.

- M2 adds savings accounts, individual money market accounts, and CDs of less than $100,000.

These are reasonable reflections of the actual cash in circulation, or what the average person has available. The big thing missing here is the banks. A separate money classification—MB, or the monetary base—includes cash in circulation, cash at banks, and Federal Reserve bank credit that banks have access to but do not have in their physical control.

In other words, MB is the amount of money that banks have to create actual consumer money. This is the most liquid measure of money, but largely in its potential. The economy depends on the banks to translate MB into money that is working in the economy. The reserves aren’t actually part of the economy until the banks lend them out; therefore, they don’t show up in the usable money stock (M1 or M2) and don’t typically factor into money velocity calculations.

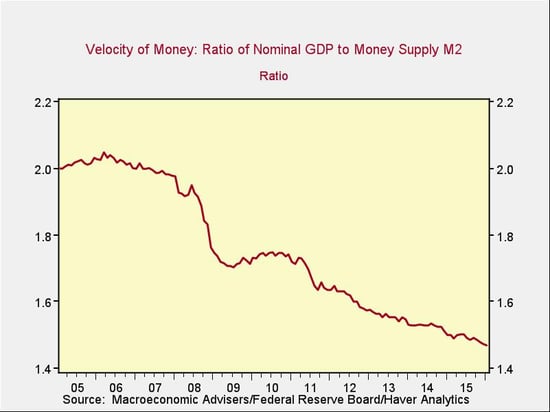

Velocity of money: Now that we have a grip on money stock, let's move on to the velocity of money, which is defined as the price level times the number of transactions, divided by the money stock. More simply, this is the economy as a whole (i.e., the gross domestic product) divided by the money stock.

Changes in money velocity are a function of two things: how fast the economy is growing and how fast the money supply is growing. You have to consider both. The reason to worry over a declining money velocity is if it reflects a shrinking economy. If, on the other hand, the declining velocity is due to the money supply growing faster than a growing economy, this should indicate a growth problem. Of course, that might lead to other problems, such as inflation, but it is not the current worry.

Is there reason for concern?

Let’s take a look at the two components of money velocity.

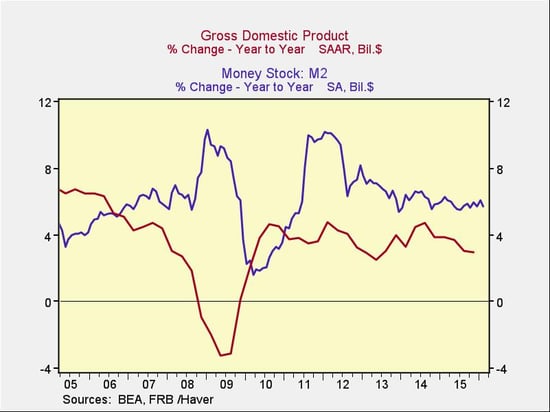

GDP growth, while not great, continues to chug along.

There is no sign of collapse, so any decline in money velocity over the past five years is not due to a drop in the economy.

Growth in the money stock, on the other hand, has spiked twice in the past 10 years and continues to outpace growth in the economy as a whole. (I have used M2 as the more inclusive monetary number here.)

If the money velocity equation is GDP/M2, and M2 is growing faster than GDP (which it is), you would expect money velocity to be on the decline. This is just what we do see over the past 10 years, as shown in the chart above. Note the substantial drops in 2008–2009 and 2011, just when the money stock spiked.

When it comes down to it, then, the decline in the velocity of money seems to be due to math rather than economic dysfunction. As always, though, it may not be that simple. Tomorrow, we’ll consider whether the increase in the money supply itself might be either a signal or a cause of future trouble.

Print

Print