Today’s post is brought to you by Rob Kane, a senior investment research analyst on Commonwealth’s Investment Management and Research team. Over to you, Rob!

Today’s post is brought to you by Rob Kane, a senior investment research analyst on Commonwealth’s Investment Management and Research team. Over to you, Rob!

It’s that time of year when holiday parties fill our calendars and small talk with new friends often leads to a common question: “What is it that you do for work?” For me, it’s a simple question that can be met with a simple answer: “I work in alternative investments.” Inevitably, though, I get the follow-up questions: “What are alternative investments?” “What makes them different?” “I often hear about them, but how do they make money?” So, for those of you wondering exactly what it means to work in alternative investments, let’s take a closer look.

What are alternatives?

Here, I could give a long response filled with intricacies and financial jargon. But really, the answer is straightforward: alternatives are investments that fall outside of traditional investments (e.g., publicly listed stocks, bonds, and cash) or investments that use nontraditional approaches to make money (e.g., shorting a stock). Simple, right?

How do alternatives make money?

But if we know what an alternative investment is by what it is not, that actually doesn’t tell us much. The real answer is based on the most important question that investors should be asking about any investment: how does it make money? For stocks, companies sell things and make a profit, which they pay to their shareholders. For bonds, an investor loans money out and then gets paid back. How, then, do alternatives make money if not in those ways? It’s a good question. The answer comes down to the fact that alternatives do things that public investments can’t, mainly, provide funds when public markets will not and exploit market inefficiencies in private markets.

Let’s look at some examples. As investors, we appreciate being able to sell things quickly at a good price, which is known as liquidity. Having an investment that can be sold quickly without negatively affecting its price allows us to maximize our return and turns paper gains into real cash in our accounts. But there are times when you can’t sell that investment quickly. At such times, a nonpublic investor might step in to buy it from you. That investor will get a great price and, ultimately, you will get a better price than you would have otherwise. Looking at it another way, alternative investments can buy things that most people won’t, with the expectation of selling them eventually. As they are now taking control of the position, shouldn’t they expect a higher return for the lack of liquidity? Your answer, hopefully, is a resounding “yes!” The potential extra return is what we call the “illiquidity premium” associated with the private markets in which alternative investments invest.

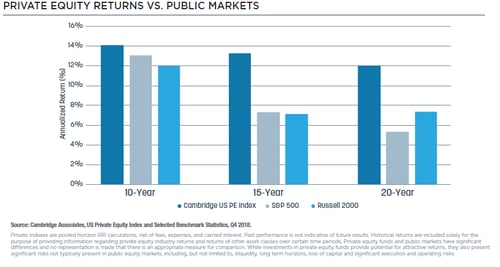

The extra compensation received from an illiquid investment can be quite meaningful. In the case of private equity, such annual returns can often be 3 percent to 5 percent over what the S&P 500 earns. Much of this return comes from public investors’ tendency to sell during volatile times, giving the private investor a chance to buy cheap.

What about market inefficiency?

Public markets are characterized by a vast number of investors, low transaction costs, and information on just about any security at our fingertips. All relevant information is (in theory) reflected in the price of public securities; therefore, markets are efficient and can’t be beat by investors! Whether you subscribe to the efficient market theory or not, the fact is that it doesn’t apply to private markets because they are inefficient.

Private markets are associated with pricing anomalies that can be exploited by savvy investors. Why? There is a relatively small number of investors, the transaction costs are high, and information, in general, is hard to obtain for the typical investor. Here, office buildings are a good example. There aren’t that many of them, there are a limited number of buyers, and each one is different. Same for companies. It is no surprise that real estate (which buys buildings) and private equity (which buys companies) are two of the biggest categories of alternative investments.

How does this work in the real world?

All of this sounds great in theory. Fortunately, it also plays out in the real world. It’s one thing to explain such concepts. But, for me at least, the proof needs to be evident in actual returns. Turning back to private equity as an example, we can see the potential long-term benefits that an investor may be able to obtain by investing in the private markets, with the index for the asset class well above the returns of stocks. The premium this kind of investment can get is real and material.

Source: iCapital Network

And that, in a nutshell, is what it means to work in alternative investments.

Print

Print