Today, the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (the FOMC or Fed) starts. It will conclude tomorrow with an announcement about interest rates, followed by a press conference. Markets expect the Fed to raise rates by one-quarter of a percentage point. This rise is fully priced into the market, which also expects an increase in December. So far, so good. These increases reflect continued economic growth and the rise in inflation to a more normal level, closer to Fed targets. In fact, the Fed raising rates is a sign of success, and failure to raise rates would cause much more concern than the expected increase.

Today, the meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (the FOMC or Fed) starts. It will conclude tomorrow with an announcement about interest rates, followed by a press conference. Markets expect the Fed to raise rates by one-quarter of a percentage point. This rise is fully priced into the market, which also expects an increase in December. So far, so good. These increases reflect continued economic growth and the rise in inflation to a more normal level, closer to Fed targets. In fact, the Fed raising rates is a sign of success, and failure to raise rates would cause much more concern than the expected increase.

Other rate increases, however, could be more damaging. The Fed’s rate increases are well planned, well telegraphed, and under control. What we are seeing in the markets, however, is that other rates are rising as well, and those rate increases might well signal trouble ahead.

10-year U.S. Treasury

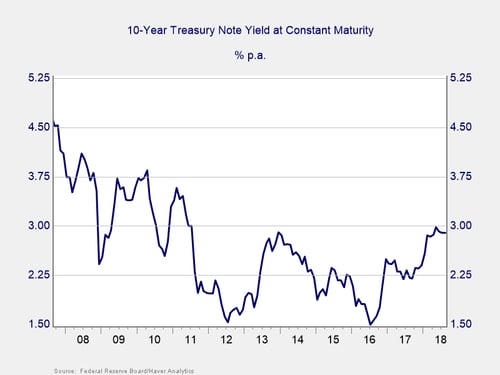

The benchmark here is the 10-year U.S. Treasury. As you can see from the chart below, yields have been below 3 percent since the start of 2011, with a brief break above 3 percent earlier this year. From this chart, the yield is now at close to the highest level since 2011, but it is still well below the 3-percent ceiling. This chart, however, is based on monthly data and misses daily volatility. In September, rates have made another sustained push to break that 3-percent ceiling.

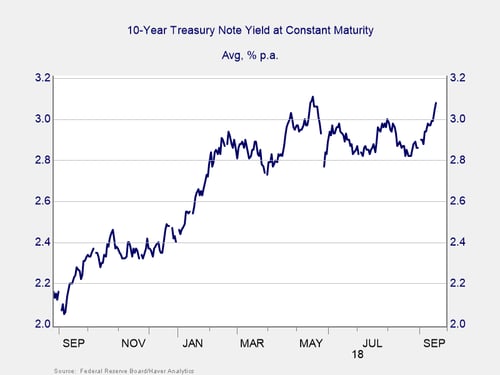

What you can see in the daily chart below, though, is how rates have stabilized between 2.8 percent and 3 percent this year. This is something we have not seen since 2013. More, rates keep pushing against and have twice broken that 3-percent ceiling, which is where they sit right now.

Rates above 3 percent on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note represent a sea change: they take us back to the higher range from before the European crisis in 2011—and may be a stepping stone to the even higher range from before the crisis. If the upward trend is sustained, it could have substantial consequences. The question we need to ask is why rates are moving higher. The answer will tell us if the trend is likely to continue.

Money: supply and demand

Money, like anything else, has a value. If you want to borrow, the price is determined by supply (how much money is available to lend) and demand (how much borrowers are looking for). One of the reasons rates were low for so long was that supplies of capital—money available—were surging. Central banks were pushing money into the system, and China and other emerging markets were recycling dollars into U.S. Treasury assets to store excess cash. Similarly, demand was low, as companies and individuals were not really looking to borrow while the economy was weak.

Now, however, the situation has reversed. Capital is flowing out of the system as central banks tighten policy. Plus, the Fed is not only tightening policy but is actually pulling money out of the system. Further limiting the available capital is the fact that China and other countries are buying much less in U.S. Treasuries. Even as supply shrinks, demand is much higher, as companies borrow for, among other things, share buybacks. With supply down and demand up, small wonder interest rates are rising as well. In both charts, you can see a sustained uptrend since 2016.

Will rates keep rising?

This brings us to the present. Will rising rates stop at 3 percent? There is nothing magic about the 3-percent ceiling, so why would they? With the trend now bumping against that level, the only thing that could keep it down is psychology—and that has severe limits in the face of supply and demand. The fact that we broke the level back in May and are now pushing above it again suggest that the forces pushing rates higher are sustained and getting stronger. When the Fed hikes rates again this week, and again in December, those forces will only get stronger.

Unless central banks loosen policy (seems unlikely) or China decides to start supplying cheap capital to the U.S. again (also unlikely), prepare for higher rates. We can see them coming.

Print

Print