Market risks come in three flavors: recession risk, economic shock risk, and risks within the market itself. So, what do these risks look like for October? Let’s take a closer look at the numbers.

Market risks come in three flavors: recession risk, economic shock risk, and risks within the market itself. So, what do these risks look like for October? Let’s take a closer look at the numbers.

Recession risk

Recessions are strongly associated with market drawdowns. Indeed, 8 of 10 bear markets have occurred during recessions. As I discussed in this month’s Economic Risk Factor Update, right now the conditions that historically have signaled a potential recession are not in place. In fact, several of the trends are improving. On an absolute basis, conditions remain good—with healthy job growth, high levels of consumer confidence, and expansionary business confidence. As such, economic factors remain at a green light.

Economic shock risk

There are two major systemic factors—the price of oil and the price of money (better known as interest rates)—that drive the economy and the financial markets, and they have a proven ability to derail them. Both have been causal factors in previous bear markets and warrant close attention.

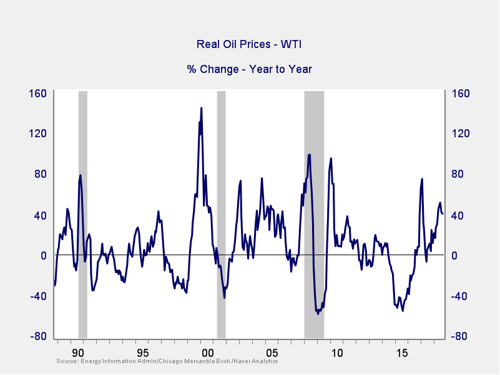

The price of oil. Typically, oil prices cause disruption when they spike. This is a warning sign of both a recession and a bear market.

A quick price spike like we saw in 2017 (it did not appear to reach a problem level and was short lived) is not necessarily an indicator of trouble. The subsequent decline also took this indicator well out of the trouble zone. Recently, prices have risen again and have started to approach a level of concern. In the past couple of months, however, the price increase turned down. Just as in 2017, while the risks from this measure are rising, they are not yet material or immediate. Therefore, the indicator remains at a green light, although we are getting closer to a high risk level.

Signal: Green light

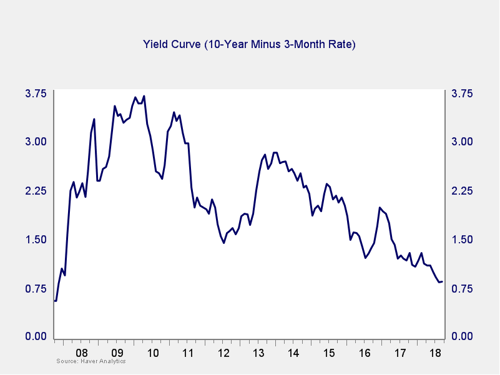

The price of money. I cover interest rates in the economic update, but they warrant a look here as well.

The yield curve spread widened a bit further in September, as longer-term rates rose to post-2011 highs, even as the Fed raised short-term rates. Although rising rates may be a concern over time, the larger spread remains well outside the trouble zone. As such, the immediate risk remains low. Arguably, the fact that longer-term rates are rising is overdue and a healthy development. But the fact of higher rates overall, in combination with the Fed’s expected rate increases, suggests that this indicator remains something to watch. I am leaving this measure at a green light for now, but you can see a shade of yellow.

Signal: Green light (with a shade of yellow)

Market risk

Beyond the economy, we can also learn quite a bit by examining the market itself. For our purposes, two things are important:

- To recognize what factors signal high risk

- To try to determine when those factors signal that risk has become an immediate, rather than theoretical, concern

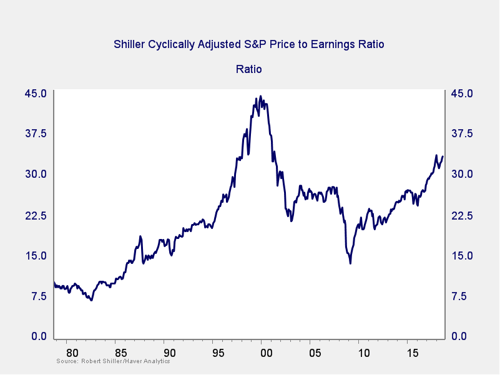

Risk factor #1: Valuation levels. When it comes to assessing valuations, I find longer-term metrics—particularly the cyclically adjusted Shiller P/E ratio, which looks at average earnings over the past 10 years—to be the most useful in determining overall risk.

The major takeaway from this chart is that valuations remain extremely high. In fact, they are close to the second-highest level of all time, exceeded only by the dot-com boom. Also worth noting, however, is the very limited effect on valuations of the recent increases in earnings due to the tax cuts. On a shorter-term basis, those earnings increases have markedly reduced valuations, suggesting reduced risk. On a longer-term basis, however, as shown in the chart above, valuations have not pulled back much at all. High valuations are associated with higher market risk—and longer-term metrics have more predictive power. So, this is definitely a sign of high risk levels.

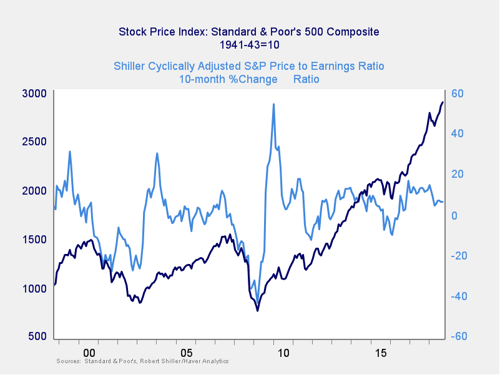

Even as the Shiller P/E ratio is a good risk indicator, however, it is a terrible timing indicator. To get a better sense of immediate risk, we look at the 10-month change in valuations. Looking at changes, rather than absolute levels, gives a sense of the immediate risk level, as turning points often coincide with changes in market trends.

Here, you can see that when valuations roll over, with the change dropping below zero over a 10-month or 200-day period, the market itself typically drops shortly thereafter. In recent months, valuation changes have dropped toward the risk zone, but they may have stabilized in the past couple of months. While the long-term trend in valuations remains at a positive level, risks are rising. Therefore, this indicator stays at a yellow light.

Signal: Yellow light

Risk factor #2: Margin debt. Another indicator of potential trouble is margin debt.

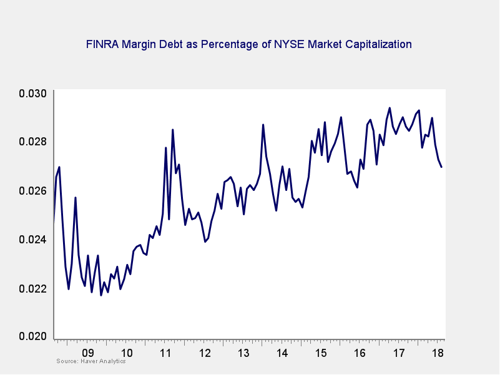

Debt levels as a percentage of market capitalization ticked further down last month, but they remain close to all-time highs. The overall high levels of debt are concerning; however, as noted above, high risk is not immediate risk.

For immediate risk, changes in margin debt over a longer period are a better indicator than the level of that debt. Consistent with this, if we look at the change over time, spikes in debt levels typically precede a drawdown.

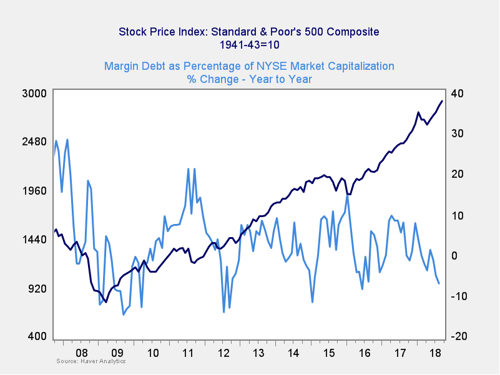

As you can see in the chart above, the annual change in debt as a percentage of market capitalization has ticked down again, moving below zero over the past couple of months. This indicator is not signaling immediate risk and, in fact, is showing decreasing risk. Still, the overall debt level remains very high. As such, the risk level is worth watching, although there has been some improvement. We are keeping this indicator at a yellow light.

Signal: Yellow light

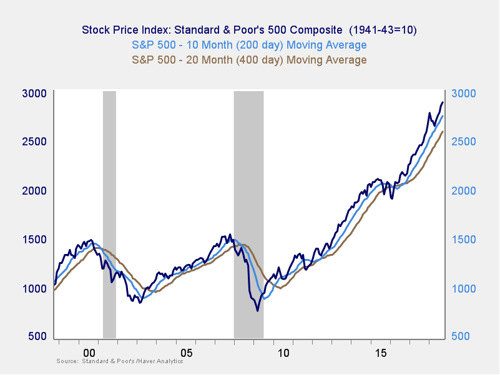

Risk factor #3: Technical factors. A good way to track overall market trends is to review the current level versus recent performance. Two metrics I follow are the 200- and 400-day moving averages. I start to pay attention when a market breaks through its 200-day average, and a break through the 400-day often signals further trouble ahead.

These indicators remain positive, with all three major U.S. indices above both trend lines. The Dow did briefly drop through its 200-day in June. In the past couple of months, we have also seen the S&P 500 bounce off its 200-day on a daily basis several times, which could be a sign of weakness. But looking at monthly signals, as this chart does, there has not been a sustained break. With no convincing movement either way, the risk of the trend turning negative has risen materially. The most probable case is that the markets continue to rise, as they failed to break support even at the nadir, and this case has been supported by the recent move back to all-time highs. But given the fact that both the Dow and the S&P recently hit their support levels—and that the rebound has been modest—risks of more volatility have increased. So, I am keeping this indicator at yellow.

Signal: Yellow light

Conclusion: Risks rising, conditions may be weakening

After taking the market risk indicator to a yellow light for the first time six months ago, markets have since recovered. This recovery was more or less expected. At the same time, the yellow light rating recognized that risks have risen. Despite the recovery, and the fact that we are once again close to all-time highs, those risks are still there.

The overall economic environment remains supportive, and neither of the likely shock factors is necessarily indicating immediate risk. But the continued volatility and the fact that several of the market indicators point to an elevated level of risk—combined with the ongoing policy concerns—suggest that volatility may get worse.

As such, we are keeping the overall market indicator at a yellow light. This is not a sign of immediate trouble. Indeed, the likelihood remains that the market will keep moving higher. Rather, it is a recognition that the risk level has increased materially and that, even as the market recovers, further volatility is quite likely.

Print

Print