Yesterday’s post ended with the idea that, if interest rates go up, market valuations will have to rise for many investors to meet their return goals. Based on the example we used, market valuations would have to increase by 3 percent per year for investors to see their required returns.

Yesterday’s post ended with the idea that, if interest rates go up, market valuations will have to rise for many investors to meet their return goals. Based on the example we used, market valuations would have to increase by 3 percent per year for investors to see their required returns.

Is that likely to happen? Let’s start by taking a step back.

What valuations really mean

The inverse of a stock’s P/E ratio is the earnings yield—that is, the return you’d see if you bought the whole company and just pocketed the earnings. With valuations for the S&P 500 at around 17x expected earnings over the next 12 months, that puts the earnings yield at around 6 percent to 7 percent. The more expensive the market, the lower the earnings yield.

Comparing the earnings yield with government bond yields, as we did yesterday, there's about a 4-percent differential. That’s basically in line with our estimated equity risk premium from yesterday, although it’s a bit low. Let’s assume that difference stays the same, and interest rates increase. In that case, we would need an earnings yield of around 8 percent to 9 percent. Flip that over, and you get an equivalent P/E ratio of around 12x to 13x expected earnings. You can argue over the exact numbers, but the valuation is well below the level we see now.

Time to start paying attention

With stock market valuations where they are now, investors may need the market to get more expensive in order to meet their return goals. At the same time, the math suggests that, with interest rate increases very likely, the market will probably get less expensive. In other words, investors now need a tailwind from rising valuations but are likely to get a headwind.

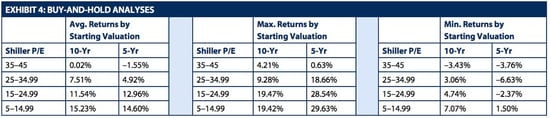

Looking back at history, this explains why returns from buying when the market is expensive have been lower than returns from buying when the market is cheap. When you buy cheap, you can get the tailwind from rising valuations; when you buy expensive, you get the headwind. You can see exactly that in the following chart.

What does this mean for investors today? Two takeaways stand out to me here:

- Valuations matter, and returns from U.S. stocks are likely to underperform over the next several years.

- Investors should seek exposure to cheaper assets. Right now, that includes international markets, among others.

A number of investors I've spoken with recently feel that it simply makes no sense to invest anywhere other than the U.S. Many people point to strong returns in U.S. markets, relatively weak returns abroad, and the fact that investing outside the U.S. would have been a bad decision over the past several years.

That, however, is precisely the point. Strong returns over a period of years create prime conditions to start moving money out of a particular asset class. Years of gains often leave markets at higher valuations. Exactly when you feel most confident about an asset class is probably the time to be most concerned. Right now, most investors love the U.S. and hate international markets. It may be time to reverse that sentiment.

It’s no accident that I’ve written about these issues repeatedly in recent months, but hopefully the math will provide some context for how this works and why. Right now, we need to keep our expectations (and especially our emotions) in check. It’s a time to think carefully about the future, which may well be very different from the recent past.

Print

Print