Today's post is from Anuradha Gaggar of Commonwealth’s Investment Research team.

Today's post is from Anuradha Gaggar of Commonwealth’s Investment Research team.

The recent market turmoil has prompted much soul-searching among emerging markets investors: can they continue to justify an allocation to the asset class?

Emerging markets make up a very small portion of most portfolios—probably not enough to move the needle significantly but more than enough to raise eyebrows when volatility strikes.

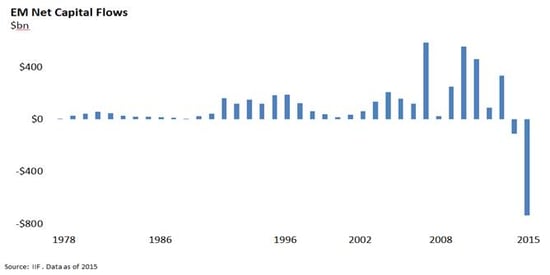

Investors haven’t really been rewarded for the risks they’ve taken on emerging markets in the last 10 years. The asset class took a turn for the worse in 2013, but the real inflection point occurred in 2011, when the margin between emerging and developed market growth started to narrow. Consequently, investors have been losing faith, pulling funds out of the emerging markets over the last couple of years.

China’s woes plague EM universe

Undoubtedly, China is the biggest culprit in the EM world right now. In the last five years, the country has surpassed the U.S. as the largest driver of global GDP growth. So it’s no wonder that, when China sneezes, the rest of the world catches a cold.

A few key issues plaguing China are spilling over to the rest of the emerging market universe, as well as the developed markets.

Too much leverage. First is the extreme level of corporate leverage that emerging markets, particularly China, have accumulated since the last financial crisis. Even without a credit event, a prolonged corporate deleveraging looks inevitable, which would result in slower EM growth.

Deflation. Another thorny issue in emerging markets is deflationary pressures. During the investment-led growth phase, China accumulated surplus capacity in many industries, which is likely heading to other emerging and developed markets.

Further, despite all the noise created by a relatively modest devaluation of the remnimbi, it is still pretty expensive with respect to other EM currencies. Even against the trade-weighted basket, it hasn’t budged much yet, and the People’s Bank of China will eventually need to narrow that gap. By some estimates, the remnimbi might depreciate by as much as 15 percent in 2016. If that happens, it would essentially mean that Chinese goods get even cheaper in the rest of the world, adding to the current deflationary pressures.

Tougher business environment. Finally, at a more micro level, the operating environment in Asia is getting tougher. Returns on capital are falling at a brisk pace, and EPS estimates keep getting revised downward.

Pockets of opportunity may exist, however

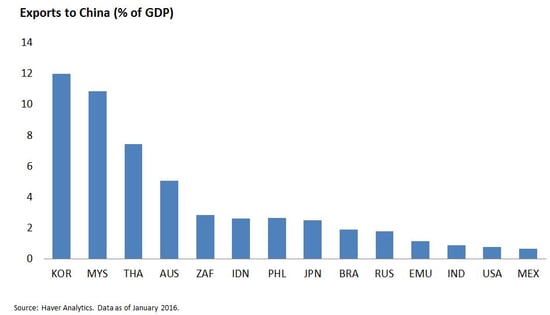

Given the grim picture in China, which other countries might fall in the eye of the storm? As you can see in the chart below, its EM neighbors are the most closely linked, but almost every major country or region has economic ties to China.

Although fundamentals remain challenged for China, Brazil, and other commodity-driven emerging economies, the very same fundamentals could present pockets of opportunity in countries like India, Indonesia, the Philippines, Mexico, and a few Central European countries.

India, for one, appears to be better positioned than most of the major EM countries at the moment. The reform agenda of Narendra Modi's government is very market-friendly. India is an importer of oil, and the lower for longer outlook for oil prices will help its economy. India does not face the demographic challenge that most of the developed markets and China are waking up to, and the weaker currency is helpful for Indian exports.

Most of these factors are already priced in, however, with India trading at richer valuations than the rest of the EM world. The initial euphoria of the new government has died down, as reforms are taking much longer to implement than anticipated. Further, India still suffers from infrastructure challenges that can act as an impediment to business growth.

In all, the domestic consumption story in India remains attractive, but the political picture looks less appealing than a year ago. Investors could find worthwhile entry points should the weakness in the asset class result in multiples contractions for Indian equities.

A challenging (but potentially rewarding) long-term play

The near-term fundamental backdrop for emerging markets remains challenging, and technical conditions are still fragile. As a result of recent EM weakness, many markets have had major (but not yet recession-level) corrections. Nevertheless, from a longer-term investment horizon, and if mean reversion has any validity, the EM asset class has started to look more and more attractive.

Further flushing remains possible, but we are not in the game of timing the market and trying to catch the bottom. To succeed in emerging markets investing at this juncture, it is essential to identify countries and sectors that will endure less pain or rebound better—in terms of both time and magnitude—because the difference between the performance of the top and bottom quintiles of EM countries and sectors will likely become even more pronounced.

Print

Print