After Wednesday’s post on why many investment portfolios are doing badly, the natural follow-up question is, how do we get them to do better? Everyone, me included, would like to be able to buy into asset classes that will do well and avoid those that won’t.

After Wednesday’s post on why many investment portfolios are doing badly, the natural follow-up question is, how do we get them to do better? Everyone, me included, would like to be able to buy into asset classes that will do well and avoid those that won’t.

If only it were that simple.

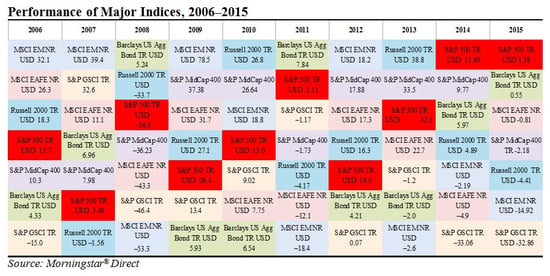

Let’s take another look at the performance of major asset classes over the last 10 years. Emerging markets, for example, regularly rotated between being the best performer (in 2006, 2007, 2009, and 2012) and the worst performer (in 2008, 2011, and 2013). U.S. bonds did the same kind of switch, from best in 2008 to worst in 2009 and 2010. You can see this up-and-down performance, although not as extreme, in every asset class.

With so much bouncing around, it’s hard to predict what will do well. Buying what worked last year has generally been a bad idea, as the chart shows. Buying what did worst last year—although it doesn't work regularly—is a much better bet than buying what did best.

The key to successful investing, as the cliché goes, is to buy low and sell high. Our goal is to buy the assets that do well and not buy those that don’t. Is it possible to combine these ideas and get better results? Over the long term, it can be.

Diversify and rebalance—a sound investment mantra

When you regularly rebalance your portfolio, you are both selling high and buying low and shifting your investments from those that are less likely to outperform to those that are more likely to do so.

Imagine it's the end of 2010, and your small-cap stocks (the Russell 2000 slot in the chart above) have done very well, while your bond holdings (the Barclays US Agg Bond slot) have not. By selling some of the small-cap stocks and investing in bonds, you would end up having more of what worked best and less of what worked less well in 2011. You would have sold high and bought low, and your portfolio would have more of what worked well and less of what didn't do so well.

In other words, you would have done exactly what every investor wants to do.

It doesn't always play out that way, of course. But simply by looking at the chart, you can see it works more often than not. Over time, this strategy can add up to significantly better results than trying to chase last year’s winners.

Even better, if you diversify among all of the asset classes, you minimize the effects when one does something unusual. For example, when U.S. bonds underperformed in 2009–2010 and 2012–2013, having a diversified portfolio helped minimize that underperformance, positioning investors to benefit from the relative gains in 2011 and 2014, without suffering as much of the damage of the previous down periods.

Making volatility work for you

Unfortunately, the simple strategy of maintaining a diversified portfolio with regular rebalancing is surprisingly hard to execute. There is something deep inside us that protests selling a winner to buy a loser. It is counterintuitive, psychologically difficult, and unpleasant. And, as we discussed on Wednesday, it doesn’t work every year, which makes it even harder to stay the course.

Right now, for example, based on 2015’s results, a rebalance would involve selling large stocks in the U.S. (S&P 500) and developed markets like Europe and Japan (MSCI EAFE), along with U.S. bonds, and buying into small U.S. stocks, emerging markets (MSCI EMNR), and commodities (S&P GSCI).

This might seem scary on the face of it, but that’s kind of the point. Comfortable assets get expensive. Scary assets are cheap because no one wants to own them.

Which brings us back to the psychological challenges of diversification and rebalancing. Yes, it seems to defy logic. Yes, you don’t really want to do it. And yes, results are not guaranteed on a year-to-year basis. It is hard to do.

In fact, the only real argument for doing it is that, over time, it can work.

Print

Print