There’s no getting around it: the jobs report, with only 20,000 jobs added last month across the entire U.S., stinks. This is a terrible report, and it should strike fear and loathing into the hearts of every economist and citizen in the country. This opinion is the bulk of what I suspect you will be hearing, and it is largely correct.

There’s no getting around it: the jobs report, with only 20,000 jobs added last month across the entire U.S., stinks. This is a terrible report, and it should strike fear and loathing into the hearts of every economist and citizen in the country. This opinion is the bulk of what I suspect you will be hearing, and it is largely correct.

But a disappointing report isn’t necessarily the end of the world.

A historical perspective

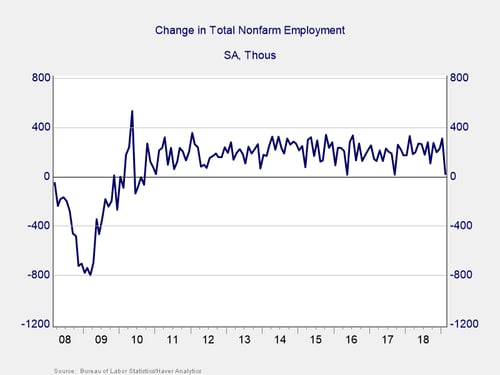

Let’s start with history. In the past couple of years, as you can see in the chart below, we have seen two months with similarly weak jobs reports. In September 2017, only 18,000 jobs were created; in May 2016, only 15,000 jobs were created. In the months that followed, however, job creation rebounded to 260,000 and 282,000, respectively. So, one bad month may end up being just that—one bad month—rather than something worse.

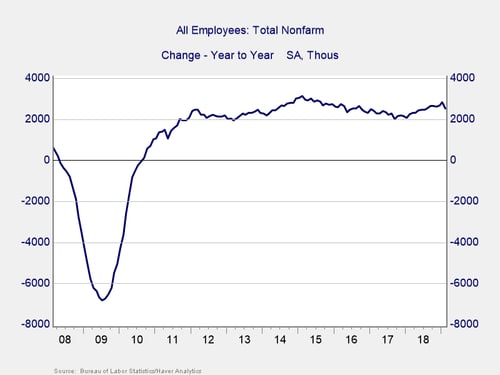

Annual change in employment

To get a sense of whether that may be the case, the annual change in employment is a better indicator, as it washes out some of the monthly variability. February’s terrible job creation number still leaves us with more than 2.5 million new jobs in the preceding 12 months, which is at or above where we were for most of the past three years. The labor market remains quite strong, one weak month notwithstanding.

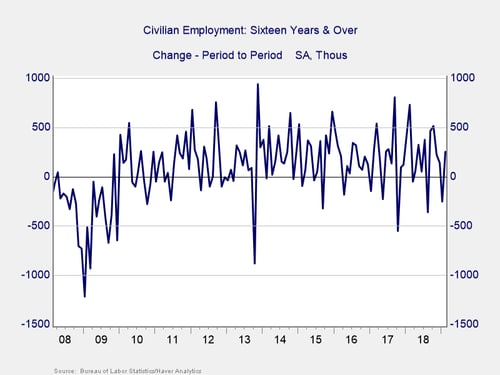

This strength is supported by the household survey, the other employment data set that gives us the unemployment rate. This survey is a different way of looking at the job market from the more business-oriented establishment survey, which is usually quoted. Here, we see that there were 250,000 jobs created last month—not 20,000.

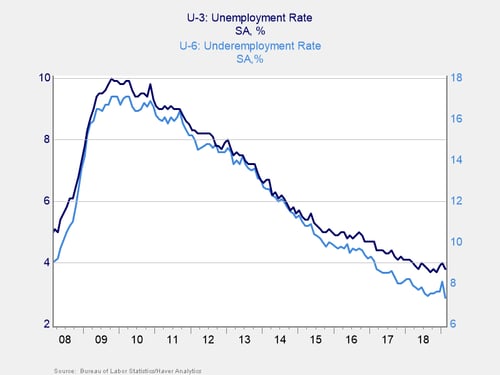

We also see from this survey that both the unemployment rate and the underemployment rate dropped last month. Further, wage growth continues to accelerate, which is consistent with a strong labor market. With all of this positive data contradicting the weak headline number, we have to suspect that this month is an outlier, rather than something worse.

Weak results an outlier?

In fact, I suspect these results may be an outlier, due to a delayed response to the government shutdown and other political turmoil. As an example, in the past couple of months, we saw both consumer and business confidence take substantial hits, only to recover the following month. Employment, which would be affected by both of these, would naturally follow after a delay and would explain this month’s drop. If so, however, it would also signal that job growth would rebound just as confidence has. Looking at the prior weak months, in September 2017 and May 2016, we saw the same pattern.

Positive trends remain

This weak report is certainly something to pay attention to and could well be a sign of further weakness to come. At the moment, though, it is simply one weak data point—just as May 2016 and September 2017 were. Job growth numbers can be quite variable on a monthly basis, as we have seen, but major trends typically shift slowly over time. Right now, the positive trends remain intact, and the supporting data continues to be quite positive.

Markets will no doubt react to the report, as they tend to do. But as we have seen in recent years, as long as the economic fundamentals remain solid, markets tend to find their way back up after an initial decline. With what we know right now, I suspect that is what we will find over the next several months as well.

Print

Print