Brad here. Today’s post on the recent volatility of the U.S. dollar comes from Anu Gaggar, senior analyst on the Investment Management and Research team here at Commonwealth. Take it away, Anu.

Brad here. Today’s post on the recent volatility of the U.S. dollar comes from Anu Gaggar, senior analyst on the Investment Management and Research team here at Commonwealth. Take it away, Anu.

Not too long ago, Brad wrote that the dollar is not going away. While that may be true, we are seeing considerable volatility in its value. What’s going on—and what does it mean for your investments? Of course, there is no crystal ball to answer such questions, but we can certainly take a deeper dive to better understand what is happening and how to deal with it.

Value is in the eye of the beholder

We started 2020 with the global economies humming along and risks skewed to the upside. The U.S. and China had signed the phase one trade deal, Brexit negotiations were finally making progress, and NAFTA's makeover in the form of USMCA (United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement) was about to enter into force.

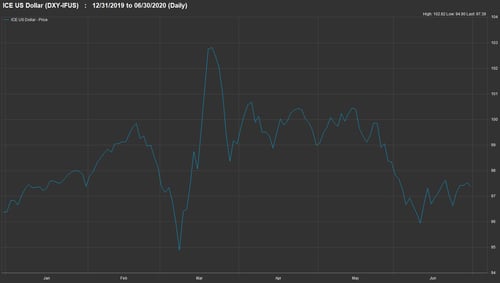

The dollar was already relatively expensive against most major currencies. But when the pandemic hit, markets panicked and rushed for what is considered one of the safest financial assets—the dollar. As a result, an expensive asset became even more expensive, with its value rising more than 8 percent in a matter of 11 days.

Lessons from Econ 101

As you know, there are only two factors that drive the price of anything: demand and supply.

When the pandemic hit, demand for goods and services across most categories collapsed, reducing the demand for the currency used to purchase them. But this collapse in demand was more than offset by the rise in demand for the dollar by businesses, government, and investors.

- Businesses attempted to draw on their credit lines to pay for fixed costs even as revenues vanished.

- Federal, state, and local governments were spending more dollars on pandemic containment measures.

- Investors rushed to the dollar to stay liquid and manage risk in what was turning into a once-in-a-lifetime black swan-like event. Investors in foreign assets liquidated their foreign holdings and converted into dollar. Foreign investors also scooped up dollars as they considered it to be safer than their own currencies.

What goes up must come down

The days of the dollar’s glory didn’t last very long. After peaking on March 20, 2020, the dollar gave up all of its gains (and then some), ending July at the lowest level since May 2018. This decline wasn’t a price collapse, just a response to the demand for dollars fading as the panic waned. While the viral spread is not yet under control, investors know that the Fed is standing ready with a backstop to minimize the effect of the pandemic on the real economy. If equity markets are any indication, risk-on sentiment is raging strong.

Beyond rising confidence, there are rising fears that U.S. consumers will ultimately pay the price for the fiscal and monetary stimulus in the form of inflation—pushing real U.S. yields below zero (if they are not there already) and pushing the value of the currency down. Finally, several countries outside the U.S. have had better luck with containing the pandemic and are already on the road to recovery. Investors, therefore, feel more comfortable allocating risk budgets to non-dollar-denominated assets. While the dollar remains solid, other options are now more attractive, reducing the demand for dollars.

On the supply side, the Fed has clearly indicated that it will continue to support the financial markets (i.e., continue to be a bottomless pit for dollar liquidity). As a result, the demand and supply curves are now crossing at lower levels for the dollar.

Source: FactSet

What does this mean for investments?

The news is surprisingly good. Overall, 40 percent of the S&P 500 revenues are sourced from outside the U.S., and a weaker dollar benefits U.S. multinational companies in two ways. First, a cheaper dollar means the prices of their products and services become more competitive globally. This can help them as they struggle through the pandemic-induced declines. Second, those foreign revenues translate into more dollars on the bottom line. Index heavyweights like Apple, Microsoft, Facebook, Netflix, and Alphabet generate less than 50 percent of their revenues each from within the U.S. Changing consumption patterns due to the pandemic boosted the fortunes of these companies. A declining dollar was an additional tailwind that led their stock prices to beat the index by a wide margin.

Beyond the U.S., when the dollar starts to weaken, it makes international equities look even more attractive. Several international markets have the wind of cheaper valuations and better control of the coronavirus cycle behind them. The euro is also benefiting from signs that European policymakers are beginning to take their relationship status one step further, from a monetary union to a fiscal union. Commodity prices rise as the dollar falls, a much-needed and opportune boost for the commodity-producing emerging markets complex. A falling dollar could thus be the panacea that international equity investors have been awaiting for more than a decade.

So, what should we do?

Currencies are just one of the many moving parts that affect equity prices, but they are certainly not the primary one. They are arguably more cyclical than many other factors; hence, in the long term, the effect of currency moves generally washes out. Thus, while currencies can have a meaningful short-term effect on portfolios, currency forecasts should not dictate how equity assets are allocated. So, if you make meaningful asset allocation moves based on your currency predictions and you get those predictions wrong? You may magnify the losses in a portfolio by being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The recent moves in the dollar are certainly eye catching. But when we look at them closely, they are easily explained by what is happening in the world. As investors, the effects may end up presenting more opportunities than threats. And, over the long term, any effects we do see are likely to wash out. Headlines can be scary, but the real takeaway here is that (as usual), stay the course even as currencies bounce around.

The U.S. Dollar Index is an index of the value of the U.S. dollar relative to a basket of foreign currencies.

Print

Print