I shared this post last spring, and I think it’s a great reminder to help us keep our expectations in check for the new year.

I shared this post last spring, and I think it’s a great reminder to help us keep our expectations in check for the new year.

The recency effect is a well-known cognitive bias in which events that have occurred most recently are given more weight than a longer-term trend. Recency bias poses a problem when it comes to evaluating investment returns—most people will only look at the last year’s returns, disregarding historical trends. They also tend to overlook long-range projections, in a forward-looking bias that might be classed as a version of the primacy effect, selective perception, or, most simply put, basic shortsightedness.

Stressing a long-term perspective

When we look at our portfolios, what we really concentrate on is performance over the past year and what we expect over the next year. The most popular stock valuation metric, the forward price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, looks at what analysts expect over the next year. Investors of a more conservative bent may consider looking at the trailing year’s P/E ratio as well. Each way, you’re looking at only one year of earnings. Focusing primarily on a two-year time frame in an investing life that can extend over decades is not optimal, at best, and just foolish at worst.

For stocks, there is a solution: the Shiller P/E ratio, which considers average earnings over a past 10-year period. This is an explicit attempt to avoid recency bias and to capture a time horizon that is meaningful over an investor’s life.

Yet there's very little attempt to capture the likely returns looking forward across an equivalent period of time. If you think about it, a single year should be almost irrelevant in the course of an investor’s life. The world didn’t end in 2009, and 2013 didn't render everyone set for life. What matters is performance over time.

Checking our figures

Some great research has been done on the issue. Jeremy Grantham and his team at Grantham Mayo van Otterloo (GMO) regularly release seven-year forecasts on asset class returns to their subscribers—and have been very successful in their projections. Ed Easterling at Crestmont Research has done yeoman’s work on identifying and quantifying the link between initial valuations and subsequent returns.

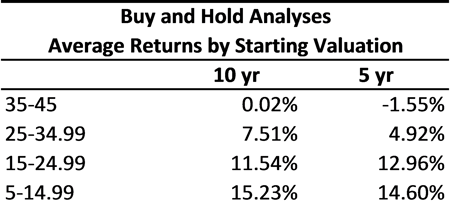

The chart below, based on my own research, shows how forward returns have varied based on starting valuations, using a Shiller P/E ratio. As of December 2015, we are at a Shiller P/E between 26 and 27, per the CAPE ratio link on Shiller's website.

You can see that the more expensive the market is, the lower your returns will be, on average, over the next 5 to 10 years. I would also note that these figures, especially for the 25–34.99 cohort, skew higher due to the inclusion of the dot-com bubble, which took values above where they’d ever been.

Adjusting expectations

Looking at the next decade or so, based on that research and the current valuation of the market, a portfolio with 60 percent stocks and 40 percent bonds would be expected to return, on average, about 5 percent per year over the next 5 years, and about 6.5 percent over the next 10 years.

Although still relatively optimistic, we have a potential mismatch between expectations and reality. This percentage is well below what most people expect, even if they are average results. Adjusting expectations accordingly could head off disappointment.

Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future performance and involve certain risks and uncertainties, which are difficult to predict. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Print

Print