Today's post is from Peter Essele, manager of Commonwealth's Investment Management and Research team.

Today's post is from Peter Essele, manager of Commonwealth's Investment Management and Research team.

The recent pullback in equity markets has brought a renewed sense of unease in an unlikely place: fixed income. These equity declines were due, in part, to inflationary concerns and the quick spike in interest rates, which sent many bond prices lower. In light of this, many investors grew worried about losing money on their bond investments and were looking for the next course of action. Before making a move, however, I would recommend taking a step back and looking at how you can actually lose money in bonds.

How can you lose money in bonds?

The two most common ways to experience permanent losses with bonds are when they default and/or are sold at a loss. Unlike equities, bonds have maturity values. This means you will get a principal value back at a predetermined date while receiving interest payments along the way. It’s really as simple as that; regardless of the investment vehicle, the math is the same. While rising interest rates can certainly affect the pricing on bonds, losses occur only if they are sold at a lower price than where they were purchased.

Here, it might be helpful to draw a comparison to the housing market. When interest rates move higher, 30-year mortgage rates most likely will too. This leads to pricing pressure and some possible declines in housing. You wouldn’t lose money, however, unless you decided to sell your house at a lower value than the purchase price. Most homeowners won’t do this because the assumption is that the house will be worth more when they eventually decide to sell. You could draw a parallel to bonds after recent declines. But the added benefit with bonds is that you already know what the end value will be!

It’s about total return

Surprisingly, an often overlooked aspect of fixed income investing is that bonds are interest-bearing instruments that will continue to pay out income until they mature. Therefore, it’s important to remember that total return includes both price movements and the income that is received. Simply put, total return = price return + income.

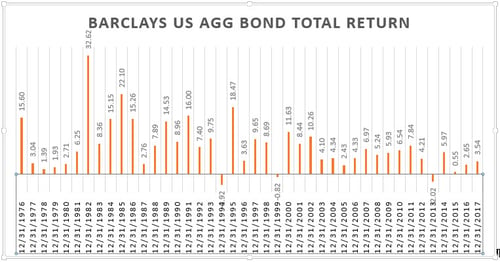

A look back at prior interest rate cycles shows that rising interest rate periods have a fairly benign impact on bond markets over the long term. As the chart below illustrates, the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Aggregate Bond Index—a broad measure of domestic fixed income—has declined in only three calendar years during its four-decade existence. The worst year was 1994, after a decline of almost 3 percent following a Fed rate hike of more than 2 percent. (This year, we’re looking at hikes amounting to 0.50 percent, maybe 0.75 percent.) Investors who rode out the storm in 1994 more than recovered the losses in 1995.

Source: Morningstar® Direct, Commonwealth Financial Network®

The positive total returns experienced by the index during rising rate periods are largely the result of the interest component, where any price declines were more than offset by the income derived. For example, if the yield on a mutual fund is 3 percent and the price moves lower by 2 percent, the total return would amount to a positive 1 percent.

One other important aspect to consider is the reinvestment of principal and interest. As rates move higher and bonds mature, they will be reinvested at higher and higher yields—which further increases the income derived. Many mutual fund managers have bonds with very short maturities. So, as rates increase, the bonds are constantly maturing and being reinvested at more attractive yields. As such, in a rising rate environment, the dividend payment received from a fixed income mutual fund should move higher as well.

All bonds are not created equal

Another factor to consider with bond investing is that not all bonds are created equal, as there are many different styles and flavors of fixed income. Examples include corporate bonds, Treasury bonds, municipal bonds, high-yield investments, and floating-rate loans, to name just a few. They all have characteristics that can influence the price of these securities beyond the overall level of interest rates.

For example, some corporate bonds, especially lower-quality names in the high-yield space, have historically exhibited positive returns during rising interest rate environments. Floating-rate securities also tend to fare well during rising rate environments because their yields can move higher with rates due to the floating aspect. Mutual fund managers typically hold a mix of these fixed income areas in order to help insulate against a rise in interest rates.

Global exposure

One way investors can reduce the interest rate sensitivity of a portfolio is through the use of foreign fixed income securities. It seems unlikely that interest rates around the world would all rise at the same time, affecting securities in the same fashion. Even though markets are becoming more integrated, a fair amount of segmentation still exists. Plus, correlations among rates in various developed and emerging countries are still somewhat muted.

For instance, if Brazilian yields were to rise as a result of inflationary pressures at a time when Germany was entering a recession, a portfolio could experience a decline on the Brazilian position and a corresponding increase from the exposure to German sovereign debt. This would effectively net out any price impact from a move in rates.

So, how should you react to rising rates?

At the end of the day, there are many things to consider when viewing your fixed income holdings in the context of rising rates, as I’ve highlighted here. The structure of a bond, maturity, geography, and credit quality can all play a part in how a bond reacts to movements in U.S. Treasury rates. In addition, it’s the income component—rather than price—that is often the most important factor to weigh when assessing total return in a rising rate environment. So, the best way to react to rising interest rates? Simply enjoy the additional yield.

Print

Print