Brad here. With the Fed widely perceived as having hit pause on rate increases, with the European Central Bank launching stimulus again, and with rates declining around the world (back into negative territory, in many cases), it is time to start thinking about what the Fed might do in the next recession. Anu Gaggar of our Research department put some relevant ideas together that we should be considering as we contemplate the next couple of years. Thanks, Anu!

Brad here. With the Fed widely perceived as having hit pause on rate increases, with the European Central Bank launching stimulus again, and with rates declining around the world (back into negative territory, in many cases), it is time to start thinking about what the Fed might do in the next recession. Anu Gaggar of our Research department put some relevant ideas together that we should be considering as we contemplate the next couple of years. Thanks, Anu!

The Fed approach

At its January 30 Federal Open Market Committee meeting, the Fed took a dovish stance by keeping the federal funds rate unchanged and indicating that it might end the balance sheet runoff sooner than expected. Fed officials did not signal that rate cuts were on the horizon, but some economists are already predicting that they are coming. On February 4, Vasco Cúrdia, a research advisor in the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, published a letter titled, How Much Could Negative Rates Have Helped the Recovery? His premise was that the U.S. would likely have recovered faster from the Great Recession if the Fed had not applied a constraint of 0 percent on policy rates. A few other recent research papers from Fed district banks have also alluded to breaking the lower bound to rates as a policy tool.

It is likely that the timing of the publications is coincidental. But it appears that Fed officials are already devising a strategy for their upcoming rate reduction cycle. Given the differences in approaches that the Fed and central banks in other developed nations took after the Great Recession, it is worth exploring whether the Fed will stick with its tried-and-tested approach or take a page from its counterparts’ playbook.

The central bank approach

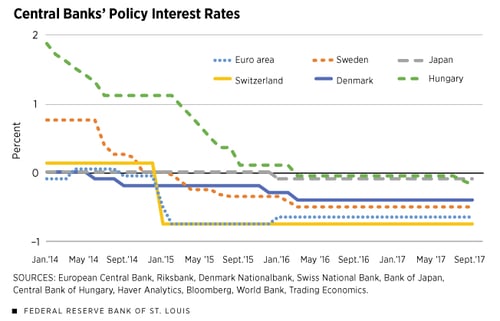

Given the depth of the last recession and the weakness of the ensuing recovery, many central banks resorted to unconventional monetary policy moves. In several advanced economies, central banks lowered policy rates to 0 percent and initiated quantitative easing through large-scale asset purchases. When these efforts failed to sufficiently stimulate their economies, central banks in the Euro area, Japan, Switzerland, Sweden, Hungary, and Denmark resorted to a negative interest rate policy (NIRP). Under this policy, commercial banks have to pay the central banks for money held at those banks, and depositors have to pay the banks to hold their cash. As absurd as this policy may sound, central banks were willing to experiment with it to incentivize banks to lend money more freely and encourage businesses and individuals to invest, lend, and spend money rather than pay a fee to keep it safe.

The negative interest rate solution

In a conventional interest rate cycle, central banks cut policy rate—typically the overnight lending rate—to ease the burden on debtors and lower hurdle rates for investment. Conventional monetary policy also assumes that the policy rate cannot go below 0 percent because individuals, corporations, and banks have the option to hoard cash instead of paying to lend out their money. Thus, a negative interest rate situation is akin to a liquidity trap since any further rate cuts below 0 percent will not stimulate the economy.

This scenario, however, assumes that there is no cost to holding cash. But we know that this is not the case. Imagine Apple storing its more than $120 billion in cash and equivalents in physical bills! Most individuals would not be comfortable keeping cash under their mattresses either. Thus, it is likely that nominal interest rates can go negative without getting into a liquidity trap.

But a negative interest rate might not be enough to stimulate the economy if the outlook for inflation and growth is dire. Simply put, if spenders believe they will be able to buy more for the same amount of money in the future, they will put off spending even if they must pay a small fee for their savings. Indeed, this is the reason the Fed did not need to go down the NIRP path with other central banks. Deflation or a decline in overall price level did not emerge as a serious threat in the U.S. as it did elsewhere. So, as bad as things were in the U.S., Europe and Japan were in a deeper hole.

How far will the Fed go?

Thus, as we think about how far the Fed can go when it starts cutting rates, we need to evaluate what can cause a deflationary environment in the U.S.: a plunge in gas prices, technology-led price declines, and a spike in unemployment with a subsequent cut to paychecks are just a few. Fed officials are already talking about whether the Fed did enough to pull the U.S. economy out of a recession the last time around. Central bank counterparts elsewhere have proven that it is possible to cut rates to negative without a collapse in the financial system—which certainly opens up the possibility here as well. But whether they were successful in achieving their monetary policy goals is a discussion for another time.

Print

Print