Today's post is from Anuradha Gaggar of Commonwealth’s Investment Research team.

Today's post is from Anuradha Gaggar of Commonwealth’s Investment Research team.

Earlier this month, capital markets declined sharply at the very hint of rising tensions between the U.S. and North Korea. Now, it’s not surprising that many global citizens would be fearful at the thought of nuclear war and the far-reaching social, political, and economic effects that could result. What may be surprising, however, is that capital markets have historically been much more stoic in times of war.

Does this make financial sense?

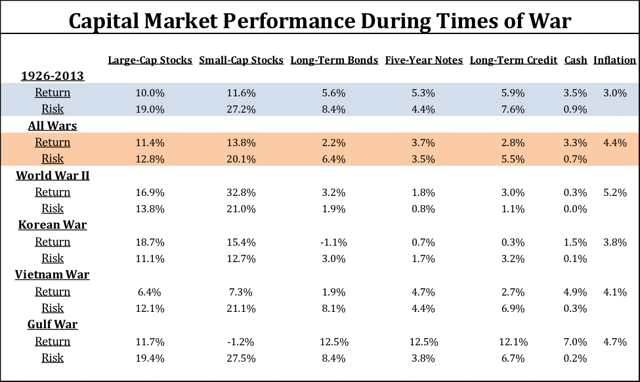

Common financial sense dictates that capital markets do not like uncertainty—which wars bring in spades. But as shown in the chart below, stock markets have done quite well (for the most part) during past wars. So-called safe-haven fixed income investments, on the other hand, have not provided quite the protection that investors expect during times of uncertainty.

Source: Mark Armbruster, "What Happens to the Market if America Goes to War?" CFA Institute Blog, 2013

Source: Mark Armbruster, "What Happens to the Market if America Goes to War?" CFA Institute Blog, 2013

As you can see, the War in Afghanistan is not included here. It went on for a longer period than other wars—commencing in 2001 and arguably ongoing—and several other factors gained prominence at different times during this period. In the shorter term, the Dow fell more than 14 percent and the S&P 500 more than 11 percent in the two weeks following the 9/11 attack. But this decline was very short lived. The Dow gained 13 percent and the S&P 500 5.6 percent in the first six months of the war. These gains came despite the fact that the war overlapped with a bear market (2000–2002) and the associated deflation of the dot-com bubble burst.

What’s behind this strong performance?

In fact, there are several potential arguments for the strong performance of stock markets in wartime. Wars bring the nation together, and this patriotic spirit may come in the form of investment in domestic companies. A more compelling argument, perhaps, is that wars magnify government spending, which results in increased revenue and earnings for those companies that are awarded government contracts. Wars also entail spending on rebuilding. From a fixed income standpoint, government spending leads to spiking inflation, resulting in rising interest rates and falling bond prices.

Why this time could be different

Nuclear threat. Wars might be good for the domestic and domestically oriented economy when combat does not occur on home ground. But in today’s world, there is a remote but real risk of a rogue nation dropping a nuke on U.S. soil. This would cause massive destruction in terms of life, property, and the economic output of our nation.

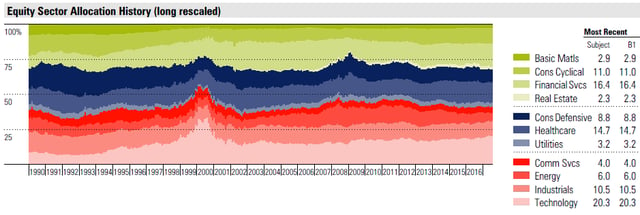

Evolving economy. The modern economy is more dependent on knowledge workers and much less so on industries like materials and heavy machinery that typically feed a warring nation. This is reflected in the equity sector allocation history of the S&P 500, as illustrated in the chart below.

Source: Morningstar

Source: Morningstar

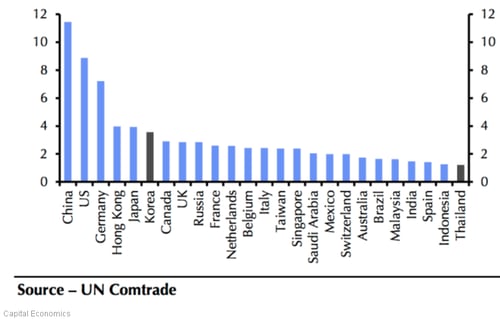

U.S. multinationals. Deeply entrenched in the global value chain, U.S. multinationals derive more than 40 percent of their revenue overseas and rely heavily on non-U.S. companies for goods and services. If, for instance, tensions in the Korean Peninsula escalate, South Korea would be the first affected. South Korea is a key element in the supply chain of several technology companies, accounting for 40 percent and 17 percent of the global supply of liquid crystal displays and semiconductors, respectively. It is also home to several major automotive manufacturers. A disruption in South Korean production would cause sustained shortages across the world.

The next chart shows South Korea’s share of global exports. You can see that the U.S. is the second-largest destination for South Korean exports. Plus, an abundance of Chinese imports from South Korea potentially would be en route to the U.S.

South Korea's share of global exports

Ongoing war. Past wars had specific start and end dates. That might not be the case for future wars. A drawn-out conflict could be a drain on the broader economy, resulting in a contraction of GDP and increased federal debt. For example, the Korean War (1950–1953) saw the South Korean GDP decline by 80 percent. Today, South Korea accounts for 2 percent of the world GDP. Thus, an economic shock in South Korea as a result of escalating tensions between its northern neighbor and the U.S. would dampen the world GDP.

After-effects. The after-effects of a war can have very different impacts on companies today than they would have had historically. We have come a long way from the use of tanks and poison gas in World War I. The war of the future will include cyber, biological, and/or nuclear attacks. These measures will be difficult to counter and entail significant outlays of cash from governments, corporations, and individuals. Returns on such investments will be difficult to evaluate and not necessarily an accretion to earnings of companies or GDPs of nations.

So, what does this mean for investors?

In the past couple of weeks, we have seen spikes in volatility based on the headlines. This could become the norm if the war of words is not contained. At the same time, it is highly unlikely that the U.S. and North Korea will actually engage in a war, as the precedent has been to resolve these tensions through diplomacy. In the shorter term, though, we could see steeper sell-offs in the historically riskier asset classes, with a corresponding flight to safety favoring defensive asset classes like gold, the U.S. dollar, Treasuries, and dividend-paying stocks.

Emerging markets, in particular, could bear the brunt of any sell-off. Nearly 70 percent of emerging markets stocks are domiciled in Asia, which, due to its proximity to North Korea, is at heightened risk. Further, emerging markets witnessed a strong rebound in the past year and a half, and investors could see this as an opportunity to take some money off the table. Similarly, developed markets outside of North America are at a greater risk than is the U.S. These markets are just finding their bearings in a slow and unsteady recovery. Any hiccup from geopolitical tensions could derail their improvement.

Past performance is not indicative of future results

We all need to be cognizant of the macro risk of potential war and its impact on economies, companies, and portfolios. Historically, wars haven’t hurt U.S. stock markets, so there is no precedent to suggest that investors should sell their holdings and go to cash or buy gold. As prudent investors, however, we need to keep in mind that past performance is not indicative of future results.

There is a very low probability, if at all, of the U.S. engaging in warfare with North Korea. As such, there is no reason to change your long-term asset allocation. But if you are concerned about heightened volatility, you may consider overweighting historically defensive asset classes as a short-term solution.

Print

Print