Today’s post comes from guest contributor Peter Essele, a portfolio manager on Commonwealth’s Preferred Portfolio Services® Select platform.

Today’s post comes from guest contributor Peter Essele, a portfolio manager on Commonwealth’s Preferred Portfolio Services® Select platform.

Like many of us, the equity markets have started 2016 with a New Year’s resolution: get in shape.

Taking a step back and looking at the post-crisis environment, it’s pretty evident that market participants have binged on the Federal Reserve’s easy-money policies for the last six years. We became complacent and lazy, and our waistlines expanded accordingly.

Spoiled by easy money

Investors got used to double-digit returns on equities. We cheered when the Fed announced round after round of injected liquidity (aka quantitative easing) in response to any pullback in the equity markets or slack in economic output. Losses were quickly recovered, and the party continued. Risk assets became the trade du jour, loss aversion was a thing of the past, and funds piled into anything that would benefit from the easy money policy—that is, everything besides cash. The Fed punished savers and rewarded those who were willing to move far out on the risk spectrum.

Investors were making money, and times were good.

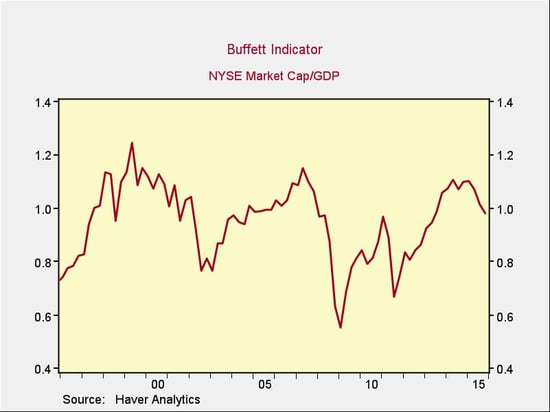

The exuberance of the last few years is summed up in the metric below—the Buffett indicator, named after the venerable titan of prognostication Warren Buffett. The index divides the market capitalization of U.S. equities by U.S. gross domestic product. Roughly speaking, you could look at this ratio as the value investors are willing to pay for the earning power of our economy, or a U.S. price-to-earnings multiple.

As the chart shows, the Buffett indicator reached post-crisis highs in the latter part of 2014 and early 2015, levels that coincide with previous peaks in the second quarters of 2007 and 1999. At the time, we were experiencing above-average equity valuation levels and all-time lows on spreads (yield over comparable Treasuries) within many areas of fixed income. Risk aversion was undoubtedly at a multiyear low.

The end of the party

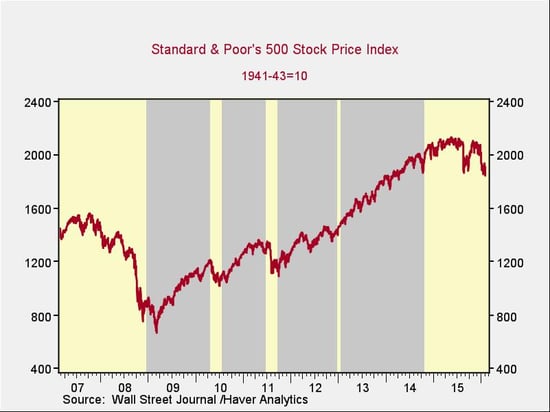

Seven years after the crisis, however, the markets have entered a period of self-reflection, asking whether the party was warranted or if it was simply irrational exuberance once again. Based on this chart, which shows the S&P 500 (red line) against periods of quantitative easing (gray areas), you’d have to argue for the latter.

This time around, we don’t have the backdrop of further easing. In fact, the Fed is currently in a tightening phase. This has left a bit of a void and put the markets on an uneasy footing, especially in light of weak economic numbers as of late. Each time we’ve seen this type of a pullback since 2008, we’ve benefited from the much-desired liquidity. This time, it’s no longer there to prop up prices.

Even if the Fed were to unveil another easing program, the positive reaction would probably be short lived. This is because each successive announcement creates an element of diminishing marginal returns, of the juice being squeezed out a little more. Such a move would likely have much less of an impact on asset prices than in previous years, nor would it do much in terms of growth, in my view.

A silver lining for patient investors

Before hitting the “sell all” button, though, it’s important to remember that volatility can breed opportunity. Many areas of the investable spectrum appear attractive as markets begin their 2016 get-in-shape campaign, and those who are willing to provide liquidity to forced sellers and take a long-term view could stand to be handily rewarded in the years to come.

The key for investors is to avoid knee-jerk reactions to market movements that could impair future goals. In fact, now may be an opportune time to take advantage of volatility by seeking out underpriced asset classes or rebalancing exposures back to long-term strategic weights.

Print

Print