The big news today in the financial world is that, for the first time on record, the yield on the German 10-year government bond dropped below zero. This is just the latest step in the ongoing decline in interest rates. In fact, the Japanese 15-year government bond recently went negative as well.

The big news today in the financial world is that, for the first time on record, the yield on the German 10-year government bond dropped below zero. This is just the latest step in the ongoing decline in interest rates. In fact, the Japanese 15-year government bond recently went negative as well.

Globally, $8.3 trillion of government debt now has negative yields. What the heck is going on?

There are two ways to look at this:

- Taking a “real-world” perspective, it could indicate that the system is broken and about to collapse. Rates this low must be a sign of disaster, right?

- From a more academic standpoint, interest rates simply reflect a market price. With supply of capital very high and demand lower, the price will continue to move down until supply matches demand.

Negative rates in the real world

What both arguments are missing is a direct connection to the economy. Negative rates operate more in the financial realm than in the real world, at least so far. In order to take the prescription of disaster seriously, we have to see if there's an actual economic connection.

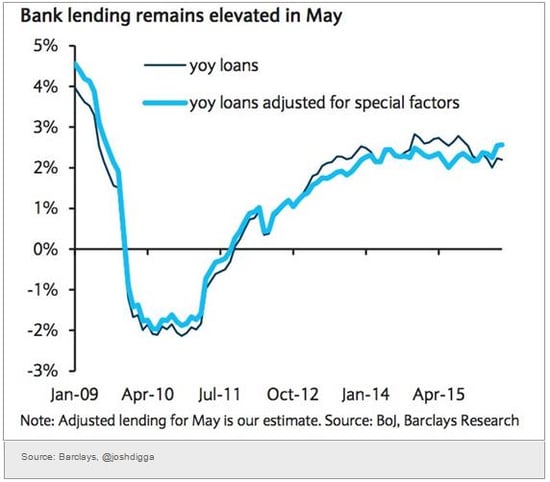

No effects on bank lending. One possibility is that negative rates might hurt bank lending. Looking at Japan, however, where negative rates are farthest along, that doesn’t seem to be the case. Bank lending continues to grow, per this chart from The Daily Shot.

In fact, lowering rates should encourage borrowing, which is exactly why central banks keep doing it. Here in the U.S., even as rates have dropped, lending has continued. This connection has not panned out.

No effects on investors’ income. Another possible connection is between negative rates and loss of income to investors, especially retirees. Here, the link is considerably more solid, but the impact is questionable in that we have seen investors continue to rotate into higher-paying assets. The effect has been to raise investors’ risk levels rather than turn their returns negative. This is certainly a problem, but not one specific to negative rates, and in any event, it has been going on for years.

The real-world case, then, remains unproven. Although negative rates don’t seem to be a good thing, they also don’t seem to be an indicator of immediate doom.

A more theoretical case: supply and demand

Next, let's look at lower rates as a factor of supply and demand, and see what dangers they may present to the larger economy. An excess of capital is actually nothing new. Large supplies of capital have been holding down interest rates since at least 2005, when Alan Greenspan himself noted declining long-term rates as a conundrum. This component, at least, is nothing new.

What is new is the constriction of the supply of high-quality assets. As the U.S. reduces its deficit, it is issuing fewer bonds, and the Federal Reserve has bought many of those. The supply of U.S. government bonds is therefore down significantly. The Japanese central bank has also been buying its own bonds, restricting supply. In Europe, the financial crisis broke the economies of many countries, leaving only a handful as good credit risks—dramatically reducing the effective supply of good bonds. In other words, even as demand has gone up, supply has contracted.

With higher demand and lower supply, is it any wonder that prices have risen? In the bond market, of course, higher prices mean lower (and even negative) yields. Rather than an indicator of economic doom, it looks to me like simple supply and demand.

Out of whack, yes, but not disastrous

That said, negative rates are still a sign that things are seriously out of whack in a financial sense. An excess of capital could come from many sources, including weak investment, and that does appear to be the case. Lack of supply comes from financial weakness around the world.

The problems are real, certainly, but overall, they look more like chronic illnesses than acute ones. That may not be much of a comfort, but it does suggest there’s still time to cure the patient. Funeral rites may be premature.

Print

Print