Following up on yesterday’s post, let’s take a look at how the income approach to retirement investing might play out in practice. (I'd like to acknowledge David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff, whose recent newsletter inspired this topic.)

Following up on yesterday’s post, let’s take a look at how the income approach to retirement investing might play out in practice. (I'd like to acknowledge David Rosenberg of Gluskin Sheff, whose recent newsletter inspired this topic.)

Bonds and the retirement investor

From an income perspective, the coupon payment is what you get from bonds. There's always interest rate risk, but absent default, there is no variability. From a capital value perspective, when the bond matures, you get your money back. If you sell before maturity, you may make capital gains (if rates have dropped) or losses (if rates have risen). If you hold a bond to maturity, however, the change in rates doesn’t matter. The point is, you get your income, which doesn’t change; then you get your money back.

For retirement investors, bonds play a valuable role as a portfolio stabilizer, particularly from a capital value perspective, and should be included in most portfolios. With rates as low as they are, however, they’re not contributing to total return in the same way they have in the past. For income, bonds may now be less useful than they have been.

Time to change how we think about stocks?

Stocks have their own problems. With valuations at very high levels, a substantial pullback at some point is quite possible. Although normal, this presents a very real hazard to retirement investors who will be drawing down their portfolios—at least from a capital value perspective.

You can hold bonds to maturity, whereas stocks are open ended. But if we’re long-term investors—which, as retirees, we should be—perhaps we might consider stocks on the same basis, as sources of income to be held indefinitely. What if we looked at stocks as an income source, as bonds have historically been evaluated, rather than as a capital asset?

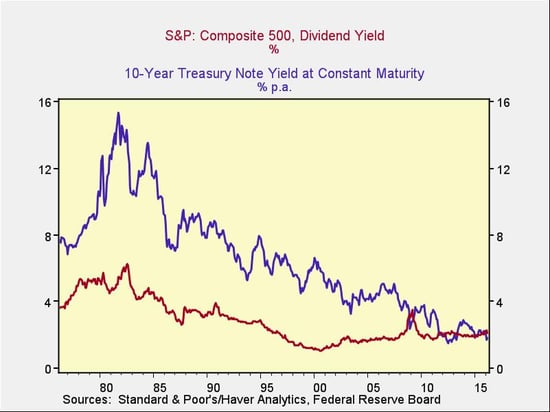

Let’s turn to the S&P 500. Right now, 65 percent of the S&P 500 companies have dividend yields that exceed the 10-year Treasury bond. The index as a whole has a yield of more than 2.1 percent, compared with 1.84 percent for the 10-year Treasury. In other words, although you cannot directly invest in an index, you can potentially get higher income with stocks than bonds.

This hasn’t always been the case, as you can see below.

Historically, income has been the province of bonds, while stocks were the place to be for capital appreciation. Where we are now is almost unprecedented in the past 30 years.

The question we have to ask is whether this is likely to continue, from both the stock and bond perspectives. Stocks are paying out more than 2 percent but are actually earning a 5-percent return at current prices. So with earnings much higher than payouts, the ability of companies, in aggregate, to keep paying their dividends seems reasonably well covered. They also have the potential to increase dividends over time, which is something a bond won’t do.

But what about risk?

The real problem in comparing bonds and stocks, though, is in the capital risk. Stocks can go down, substantially at times, while bonds typically pay fully at maturity. Does the extra income compensate for that risk?

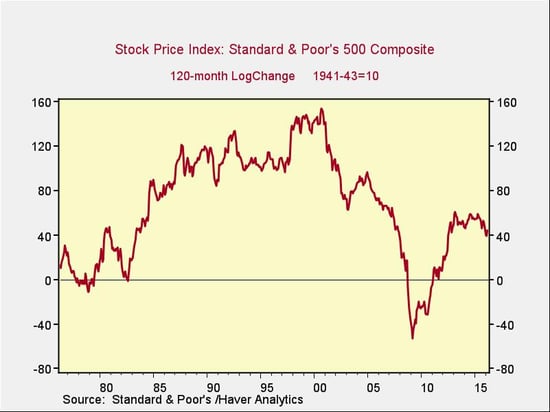

To compare the risk on something approaching an equal basis, I looked at the change in the S&P 500 over a 10-year period.

Per the chart, the only time there were substantial losses was between the 1999 market peak and the 2009 nadir—but they do happen. If you buy stocks at the wrong time, and sell stocks at the wrong time, you can lose money. It’s hard to do a similar analysis for bonds, especially during a time of decreasing interest rates, but in theory, rising rates can hit a bond as well. The difference is that holding the bond to maturity eliminates that risk.

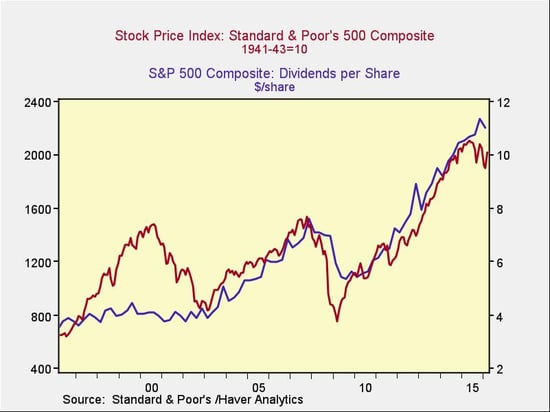

So what if we held stocks indefinitely, at least 10 years, like a bond? If so, we would certainly be exposed to capital value drops, as seen below, but from an income perspective, we would be much less exposed.

Dividend growth tends to be much less volatile than stock prices, although it can drop. In 2009, for example, stocks fell by approximately 50 percent, back to levels of 1998. At the same time, dividends, although down substantially from the peak, were still paying out about 25 percent more than they were in 1998. Looking at this from an income perspective, you get a much better view of the advantages and risks for a retiree.

Focusing on income and maintaining a long-term perspective should give you a clearer sense of how to manage your portfolio over time. As I said yesterday, I’m still thinking through these ideas, but the short-term implication is this: even at current stock prices, exposure to the market can still make sense for retirees if managed in a thoughtful way.

Bonds contain elements of both interest rate risk and credit risk. The purchase of bonds is subject to availability and market conditions. There is an inverse relationship between the price of bonds and the yield: when price goes up, yield goes down, and vice versa. Market risk is a consideration if sold or redeemed prior to maturity. Some bonds have call features that may affect income. Investments are subject to risk, including the loss of principal. Because investment return and principal value fluctuate, shares may be worth more or less than their original value. Some investments are not suitable for all investors, and there is no guarantee that any investing goal will be met. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Talk to your financial advisor before making any investing decisions.

Print

Print