Several times over the past couple of months, I’ve mentioned that, while we certainly have an unemployment problem now, changing demographics will mean that the U.S., along with most of the developed countries (and China!), will eventually have a labor shortage. Hard to believe, I know, but then again, in 2005, most people didn’t believe that the housing market could ever go down.

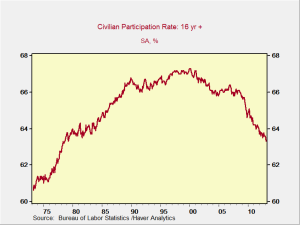

I’ve also noted many times that part of the declining unemployment rate may be due to older workers retiring (to put it at its most favorable) or simply giving up on the labor market. As workers get older, a trend that is continuing, eventually they’ll simply drop out of the labor force in one way or another.

You can see this in the declining participation rate in the labor force, shown below. The percentage of the available population that is actively engaged is at about a 30-year low now. There are multiple reasons for this, with rising disability claims being a big one, but the underlying trends are demographic.

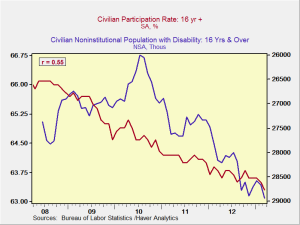

Let’s look at the disability claim part of the situation, as shown in the chart below. I have inverted the disability chart to better match the data sets—note that disability claims are rising, not falling. You can see that the disability claims line up very well with the falling participation rate.

This is not inconsistent with the aging out of the baby boomers; in fact, I see it as a supporting indicator. For many workers who are older but not yet able to legally retire, a disability claim, whether it be for back pain or depression, provides a bridge to receiving social security. Most of those workers, especially the older ones, are not coming back.

I suspect—though I haven’t seen the data—that disability claims are disproportionately high among the lower-income cohorts, which would be consistent with injury claims. It also seems reasonable that the people who actually get injured generally aren’t those working indoors in white-collar jobs.

All of this leads up to my point: Due to a declining working population and disproportionate fallout to disability, the domestic labor force for certain kinds of jobs is now declining to a level where we are seeing labor shortages. This is exacerbated by a shortage of immigrant workers, who were typically willing to fill the gap for lower-paid positions. With demographic changes in Mexico, in particular, and legal and social changes in the U.S., we will not see the same kind of labor inflows as we have in the past.

You know a trend is in place when it makes the front page of the Wall Street Journal. This one has with today’s article “As America Ages, Shortage of Help Hits Nursing Homes,” which outlines exactly the problem I’ve been describing. A quick Google search today reveals a Tampa Tribune story about the labor shortage for strawberry growers and a CBS News story from four days ago about how a farm labor shortage is hurting production.

One of the big problems with this recovery so far has been the slow rate of job creation. Although jobs are being created, the pace has been below that of previous recoveries, and this is rightly seen as a problem. Suppose, though, that job creation starts to accelerate and the working population does not. That could be a bigger problem.

Clearly, we’re a long way from worrying about too many jobs. The time to think about consequences, though, is before the problem hits. The consequences here could include higher inflation and slower growth, among others. One thing we know going forward is that the next set of problems will be different from the current set. A labor shortage is a good example of just that different kind of problem.

Print

Print