The Ukraine crisis appears to be stalled for now, with Putin—having made his point and essentially occupied the Crimea—deciding to hold there, while the Europeans determine how to proceed. This is probably where we will be for some time, and the markets seem to concur, as they have bounced right back. Move along, nothing to see here.

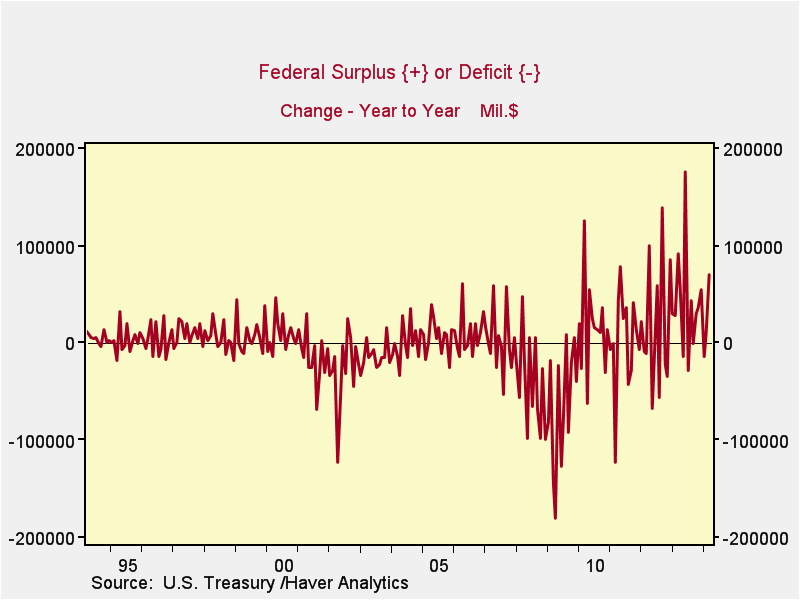

I don’t necessarily think this story is over, but for the moment, let’s return to a longer-term issue that I discussed on Friday, the U.S. budget deficit. The Congressional Budget Office’s projections are below.

I noted last week that the total deficit was expected to decrease as a percentage of the economy, but drew a distinction between the primary deficit—before interest payments—and the total. That is what I want to dig into today.

Over the next 10 years, the primary deficit is expected to drop to below 1 percent of the economy, which should be below the growth rate—meaning that the debt would shrink as a proportion of the economy. The primary deficit problem, then, is largely solved, at least based on the CBO projections.

The issue is that the primary deficit problem isn’t the actual deficit problem. While the primary deficit stabilizes, the actual deficit increases as interest payments are expected to increase. The problem we face can therefore be better understood not as a spending problem, but as an interest rate and accrued debt problem.

Understanding where the problem actually lies does not solve it, but it does help us understand the likely evolution of policy. There are two possible ways to make the situation better without cutting spending: lower the debt or maintain interest rates at lower-than-projected levels.

Arguably, there is no way to actually lower the debt. I say arguably because I wrote a piece for the CFA Institute that talked, albeit in a tongue-in-cheek sort of way, about having the Fed do exactly that. It currently holds almost $2.3 trillion in Treasury debt, per the following chart, and forgiving that would go a long way toward lowering the outstanding debt.

Unfortunately, it wouldn’t actually improve the deficit problem, because the Fed currently sends the interest payments it gets right back to the Treasury, but it was a nice thought.

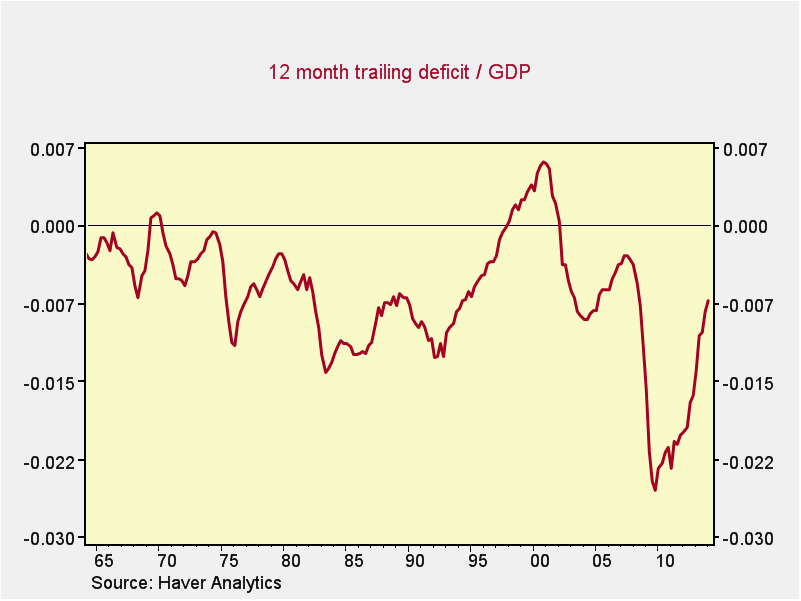

Which leaves us with interest rates. The government clearly has an incentive to keep rates as low as possible; the question is whether it has any ability to do so. History suggests that, in fact, it does. Between the Fed and the Treasury, rates remained low in the 1950s up to the mid-1960s, per the following chart. As the Fed has shown in recent years, it hasn’t lost its ability to muscle the markets into keeping interest rates low, and in the absence of rising inflation, which is where we are right now, we can reasonably expect that’s what will continue to happen.

The problem with this is the assumption that inflation remains under control. For other, non-deficit reasons, the Fed is actually trying to create inflation. At some point, it will succeed, and interest rates will go up. Solve one problem, create another.

Which brings us back to spending. The bottom line is that we continue to have a problem in the medium term, and we either have to somehow keep interest rates low or cut spending so we can spend more on interest payments. That is the real pending budget problem, and just because it won’t hit for another couple of years doesn’t mean we shouldn’t plan for it.

Print

Print